| | | | | | | Presented By HCA Healthcare | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder ·Jan 27, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,729 words, a 6½-minute read. - Send your feedback and ideas to me at alison@axios.com.

- 📚Axios' co-founders are writing a book about our smart brevity style. Pre-order begins in March.

- Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Subscribe.

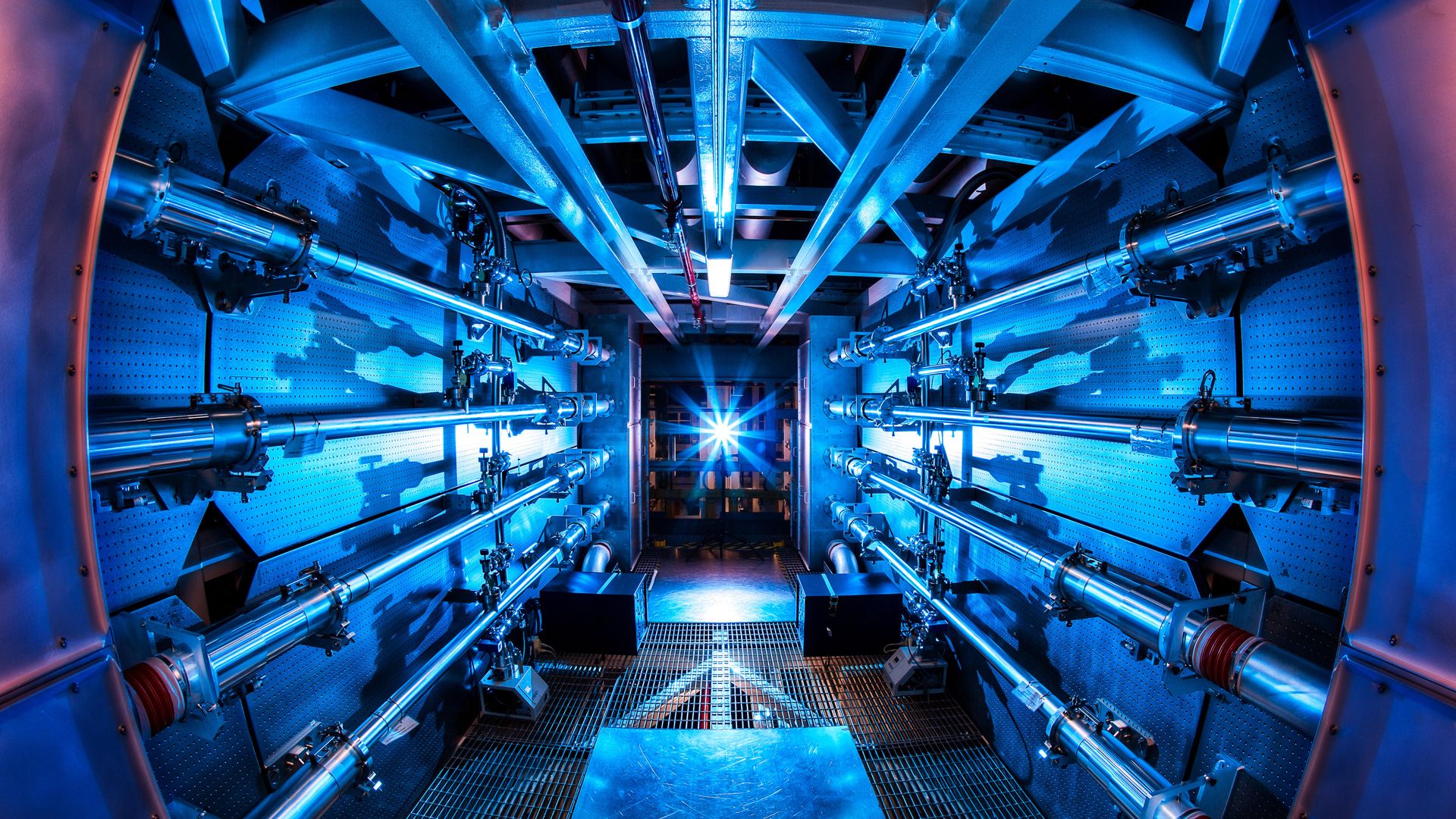

| | | | | | 1 big thing: A fusion energy milestone |  | | | Inside a support structure at NIF. Researchers there this week reported creating a self-heating plasma for the first time in a laboratory. Photo: Damien Johnson | | | | Nuclear physicists are notching scientific advances for fusion energy, fueling hopes — and billions in investment — to create an energy source that doesn't produce carbon or nuclear waste. Why it matters: For decades, scientists have chased the dream of using fusion for limitless clean energy. But turning the science into a commercial technology still faces scientific, technical and financial hurdles. The goal is to build a machine that can control nuclear fusion reactions — when the nuclei of two light atoms combine to create the nucleus of a heavier atom and generate energy in the process. - Crucially, the reactors would have to produce more energy than they require in the first place to achieve fusion.

- Researchers have tried for decades to mimic massive fusion reactions seen in stars like our Sun on a smaller scale here on Earth. They've focused on combining nuclei of deuterium and tritium, both of which are isotopes or versions of hydrogen, to create a helium nucleus — and capturing the energy released.

- The extremely hot plasma (about 100 million degrees Celsius) in which fusion reactions occur can be contained using powerful magnetic fields or by compressing the fuel using lasers or beams of particles.

- But it requires feeding the reaction a lot of energy.

Driving the news: Researchers at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory's National Ignition Facility (NIF) this week reported creating a self-heating plasma for the first time in a laboratory. - A self-heating plasma is significant because "fusion is now providing the majority of the heating," says Alex Zylstra, an experimental physicist at LLNL and an author of the study published this week in Nature.

- The next major milestone to reach is ignition, Zylstra says. That's when the fuel can keep burning on its own and the energy output from the reactions is greater than what is required for starting fusion reactions in the first place.

How they did it: NIF uses a deuterium and tritium fuel inside a polished diamond spherical capsule that is placed in a hollow container. - 192 lasers pointed at the container produce X-rays that rapidly heat and expand the capsule, compressing the fuel to pressures greater than those in the Sun to start the fusion reactions.

- In experiments performed in late 2020 and early 2021, researchers were able to generate up to 170 kilojoules of energy — equivalent to about nine 9-volt batteries.

- In follow-up experiments in August 2021 that haven't yet been published, NIF scientists produced eight times as much energy but still short of the 1.9 megajoules of energy that goes into the reaction.

"It remains unclear whether this research will lead to a viable future power source," Nigel Woolsey, a professor of physics at the University of York who wasn't involved in the research, writes in an article accompanying the new paper. - NIF's laser-fusion experiments could yield insights into the basic physics of self-heated plasma, which are used in other fusion energy approaches, and how it behaves inside stars and nuclear weapons, which the facility is specifically designed to study.

The big picture: Magnetic-fusion experiments have recently logged their own advances with the aim of producing sustainable energy. - There are more than 40 private fusion companies globally, which have raised over $2.5 billion in investment to date, according to a report from the U.K. government.

- Some scientists claim they will be able to deliver fusion energy technology within a decade. Others say it will be another 50 years.

These are all still experiments, Woolsey and Zylstra tell Axios. Read more. |     | | | | | | 2. An AI to follow instructions |  | | | Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios | | | | The next generation of a machine learning language algorithm can better understand a person's instructions and intentions, OpenAI reported in a paper posted on its site today. Why it matters: What's called "aligned" AI aims to be more honest and less toxic, biased or inappropriate — what most people consider required features for any artificial general intelligence that might be created in the future. - "As AI systems become more powerful and take on more responsibility and make more consequential decisions, it will be increasingly important that it follow the intentions of operators — stated and unstated," says OpenAI co-founder and chief scientist Ilya Sutskever.

How it works: InstructGPT is a "fine-tuned" version of GPT-3, an algorithm that predicts what word comes next in a sentence or phrase. - But that is "very different than safely and effectively doing a task the user wants to perform," says Jan Leike, who heads alignment research at OpenAI.

- For example, Leike says if you ask GPT-3 to explain the Moon landing to a 6-year-old, it might explain the theories of gravity, relativity and the Big Bang. "It's trying to guess a pattern if this was text on a random webpage."

- But InstructGPT returns: "People went to the Moon, and they took pictures of what they saw, and sent them back to the earth so we could all see them."

"To get to what humans want, [you] have to get humans in the system." — Jan Leike, OpenAI The researchers trained InstructGPT using humans who annotated and rated the models' responses to signal whether it was doing something close to what humans want. - The results suggest InstructGPT is better at following instructions and slightly less toxic but not less biased than GPT-3.

- The model is now the default one for OpenAI's API.

Yes, but: The model still makes mistakes and is "far from fully aligned." - It struggles with prompts based on false premises, and it can be overly deferential, giving multiple possible answers, even if one is clear from the context.

- InstructGPT's behavior is influenced by the human judgment it receives — and therefore the identities, beliefs and experiences of the people who train the models. More research is needed to make the models inclusive.

- And it can still create toxic or biased outputs if instructed, making it vulnerable to disinformation and underscoring the need for guardrails, Leike says.

Go deeper: The new version of GPT-3 is much better behaved (and should be less toxic (MIT Tech Review) |     | | | | | | 3. Catch up quick on COVID |  Data: N.Y. Times; Cartogram: Kavya Beheraj/Axios "New COVID infections are declining in the U.S. — a sign that the Omicron wave has likely peaked," per Axios' Sam Baker and Kavya Beheraj. Long COVID symptoms are much less likely in vaccinated people who have had COVID-19, according to a new study from Israel, Freda Kreier reports for Nature. Four biological factors — including the level of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the blood and Type 2 diabetes — are associated with whether someone develops symptoms of long COVID, The Scientist's Natalia Mesa reports on two new studies. |     | | | | | | A message from HCA Healthcare | | HCA Healthcare's $10 million commitment to advancing diversity | | |  | | | | In 2021, HCA Healthcare announced it will give $10 million to Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Hispanic-Serving Institutions. This investment will help advance diversity in healthcare by creating a more diverse talent pipeline reflective of HCA Healthcare's communities. | | | | | | 4. Needed: More sex in space for science |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | Before humans can settle off-Earth, scientists need to figure out how — or even whether — people can reproduce in space, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: Powerful figures in the space industry like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos have dreams of a future where millions of people live in space, which would naturally require a self-sustaining population of humans somewhere other than Earth. - "It has been [more than] 20 years since the last systematic experiments on vertebrate reproduction and development in spaceflight," Gary Strangman, the scientific lead at the Translational Research Institute for Space Health, told me.

What's happening: Scientists have sent a number of experiments to the International Space Station in recent years to try to answer various questions about what it might take for mammals, and eventually humans, to reproduce in space. - A study published in June found freeze-dried sperm from mice sent to the ISS weren't adversely impacted by the environment in low-Earth orbit, producing healthy pups back on Earth after its return.

- An earlier Russian experiment sent male and female rats to orbit, allowing them to breed. Two of the female rats became pregnant, but neither resulted in a live birth.

Yes, but: More in-depth studies are needed in order to figure out just what it would take for humans and other species to have babies off-Earth, and some scientists say there hasn't been enough attention paid to funding and performing these types of studies. Read the rest. |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time |  | | | An arctic hare on one of the Queen Elizabeth Islands in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, Canada, 1958. Photo: by NFB/Getty Images | | | | An Arctic hare traveled at least 388 kilometers in a record-breaking journey (Ariana Remmel — Science News) The quantum edge (Anastasiia Carrier and Chloe Fox — The Wire China [subscription]) A new Mayflower autonomously navigates the future (Alka Tripathy-Lang — Eos) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | Photo: Murugan et al., Science Advances 2022 | | | | A cocktail of compounds can coax an African clawed frogs' cells to regrow a hind limb, researchers reported this week. Why it matters: The approach could inform efforts to regenerate limbs in other animals and reveal how biological signals guide the fate of cells. How it works: Scientists placed a silicone cap containing five different chemical compounds that are found in the embryonic environment over the wound where a frog's leg was amputated. - They removed the cap after 24 hours and returned the frogs — which have the ability to regenerate limbs when they are tadpoles but lose it as they become adults —to live their tank lives for the next 18 months.

- After about four months, frogs treated with the device and compounds began to regrow new limbs, eventually with bones, nerves, muscles and toes. (Those with just the device also started to regrow, cued by the physical pressure from the device, but never to the same extent. Those without either the device or the compounds grew short spikes.)

Yes, but: It wasn't a perfect limb. It didn't have nails and the webbing between the toe projections was still abnormal. - Future research might look at the effect of longer exposure to the compounds, trying a different cocktail or periodically reapplying the device to the wound. And then there is the challenge of trying to regrow limbs in mammals.

- Limbs are very complex — the cells and genes that make them aren't fully understood, says Michael Levin, an author of the study published in Science Advances and a biologist at the Allen Discovery Institute at Tufts University.

- Guiding the animal's own cells with chemical signals is "a much more viable alternative for now" than micromanaging them with gene editing or gene therapy, he says.

The big picture: The study "shows us we can potentially kick-start latent pathways that once existed or were silenced through other developmental signals," says Nirosha Murugan, an associate professor at Algoma University in Ontario, Canada, and another author of the study. - And there could be different processes for regeneration, she says.

- In the study, leg regrowth didn't include the same exact stages seen in normal limb development.

The bottom line: "Living systems can do a lot more than what they normally do," Levin says. |     | | | | | | A message from HCA Healthcare | | HCA Healthcare strategically partners with leading tech companies | | |  | | | | HCA Healthcare, a leading provider of healthcare services with over 32 million annual patient encounters, has partnered with General Electric, Google and other technology companies. These partnerships help build innovative solutions to advance care delivery in and outside of its hospitals. | | | | Thanks to Sheryl Miller for editing this week's edition. |  | Bring the strength of Smart Brevity® to your team — more effective communications, powered by Axios HQ. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments