| | | | | | | Presented By University of Central Florida | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Apr 28, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's edition is 1,583 words, about a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Climate change could fuel future pandemics |  | | | Illustration: Shoshana Gordon/Axios | | | | Climate change will increase pressure on species to migrate and bring thousands of new chances for viruses to jump from one species to another in the coming decades, a new study reports. Why it matters: These events could increase the chance of a pandemic in humans. Ebola, HIV, bird flu, SARS — and many scientists think COVID-19 — all started with spillovers of viruses from wildlife and livestock to humans, my Axios colleague Andrew Freedman and I write. - The study, published in the journal Nature, shows how climate change and land use shifts will push pathogens' host animals to novel places where they will mingle with other species for the first time.

- These inter-species connections will expand the reservoirs for viruses, further threatening endangered species and increasing the chances of viruses spilling over to humans.

- Most of these species-to-species jumps could go undetected, the study warns, since current surveillance efforts watch exclusively for viruses jumping from wildlife to humans.

- "This [study] is really stressing that there are lots of cross species transmission events that are happening now, and many more that can happen as environments are changing," says Thomas Gillespie, a disease ecologist at Emory University who was not part of the new study.

How it works: A pathogen's ability to jump from one species to another depends on whether the hosts have a chance to interact and how similar the two host species are to one another. - Most jumps to new species are "dead ends" for viruses — they don't make their hosts sick and fail to spread. But those that do can be devastating.

What they found: The new study models how the ranges of mammal species, which are hosts to viruses that are most likely to spill over to humans, might change under different climate and land use scenarios for the year 2070. - The researchers project that among 3,139 mammal species, there could be hundreds of thousands of first encounters between species in the next five decades if warming is kept to less than 2°C above preindustrial levels.

- Those would lead to more than 4,500 transmissions of viruses from one species to another.

Details: The model also projects where these encounters will happen. - Most would take place in high-elevation ecosystems with abundant biodiversity in tropical Africa and Asia. As species move up hillsides and mountains in search of cooler temperatures, they will encounter new neighbors. Similar dynamics will play out in the dwindling tracts of species-rich tropical primary forests.

- Many of those places are also where cities are built and crops are planted.

- "Climate change is creating innumerable hotspots of future zoonotic risk or presents a zoonotic risk right now in our backyard," Colin Carlson, a disease ecologist at Georgetown University and co-author of the study, said in a press briefing, using the term "zoonosis" that refers to viruses jumping between species.

Go deeper. |     | | | | | | 2. Catch up quick on COVID |  Data: N.Y. Times; Cartogram: Kavya Beheraj/Axios "COVID cases are on the rise in all but six states and Washington, D.C., as the Omicron subvariant continues to spread across the U.S.," per Axios' Tina Reed and Kavya Beheraj. Moderna announced today that the company asked the FDA for emergency use authorization of its COVID-19 vaccine in children from six months to age 6, Axios' Erin Doherty writes. COVID is spreading among white-tailed deer in North America, but scientists aren't panicking yet, Smriti Mallapaty reports for Nature. |     | | | | | | 3. Virtual meetings' creativity cost |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | All those Zoom meetings could be stunting innovation at work. Why it matters: A new study offers data for employers grappling with how to balance the benefits of in-person work with its costs, Axios' Erica Pandey and I write. Details: In-person meetings generate more ideas — and more creative ones — compared to videoconferencing, according to new research published this week. - But choosing which idea to then pursue — a key subsequent step in brainstorming — wasn't stymied by videoconferencing, Melanie Brucks of Columbia Business School and Jonathan Levav of the Stanford Graduate School of Business report in the journal Nature.

Zoom in: In a laboratory study that started before the pandemic, more than 600 people worked in pairs in person or virtually for five minutes to come up with ideas for how to creatively use bubble wrap or a Frisbee. - Then they had a minute to pick their best idea. Judges scored the creativity of their ideas — based on novelty and value.

- They found pairs working on Zoom came up with fewer ideas.

- The same effect was seen in field studies of 1,490 engineers who paired up to brainstorm during workshops at a multinational telecommunications company.

What's happening: An often overlooked ingredient in the secret sauce of collaboration is that, in person, team members typically share visual cues from their environment — and each other — that can spur ideas. - In a virtual meeting, all eyes are focused on screens and ignore the environment, which "constrains the associative process underlying idea generation," say Brucks and Levav.

- In the laboratory study, virtual pairs spent more time looking at their partner and less time looking at the surrounding room, and remembered fewer unexpected props (a large house plant or a bowl of lemons) in the room compared to in-person pairs.

- People also move less when they meet virtually: "Staying still hinders creativity," says Jeremy Bailenson, a professor at Stanford who studies virtual human interaction.

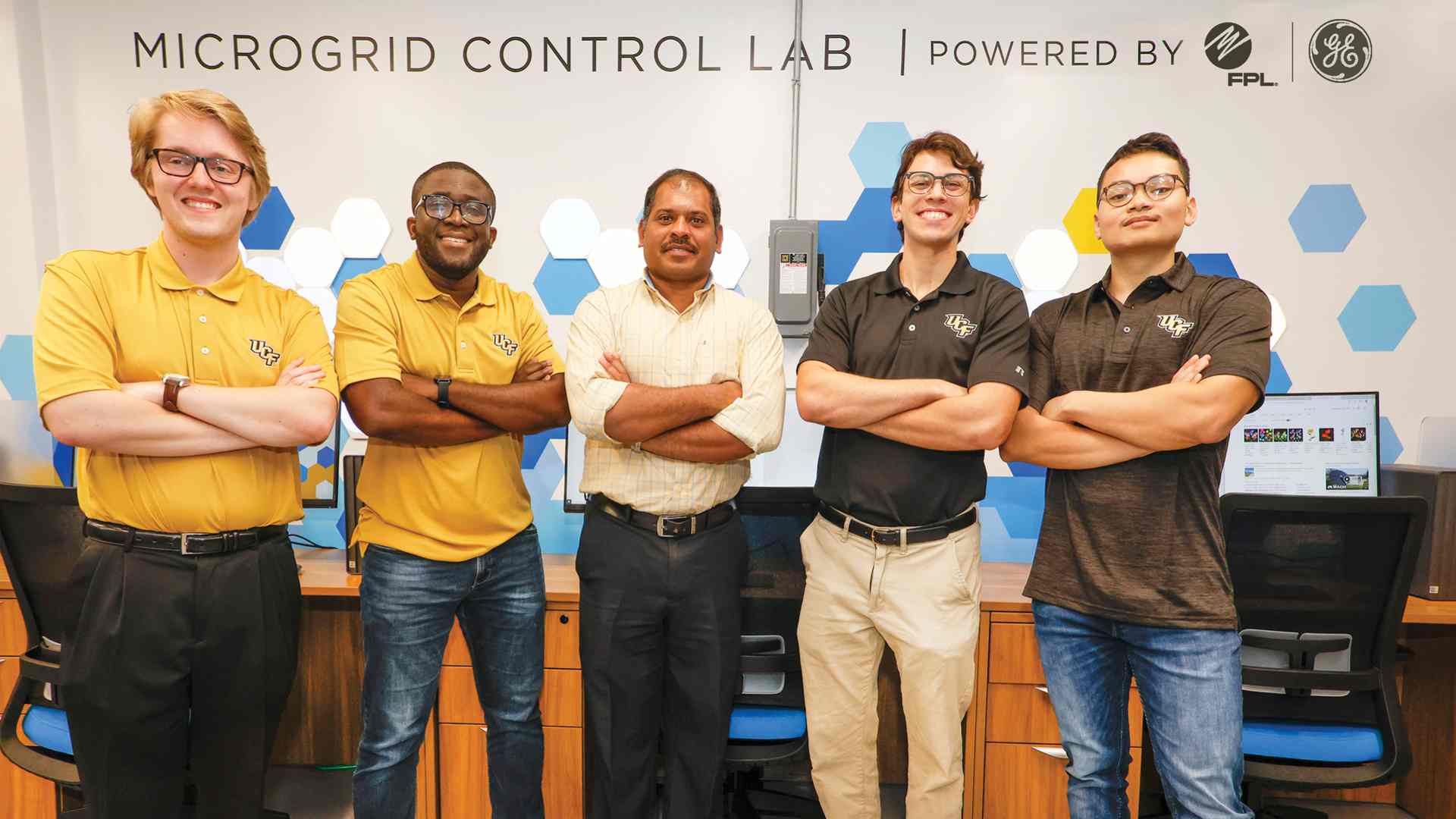

But, but, but: The study only looks at the cognitive costs of collaborating virtually, and the authors note there are "concrete and immediate economic advantages to virtual interaction," including reduced travel time and expenses, less overhead and other factors to be balanced. |     | | | | | | A message from University of Central Florida | | New research lab helps shape tomorrow's energy professionals | | |  | | | | GE Digital and Florida Power & Light Company have launched a new cutting-edge Microgrid Control Lab at the University of Central Florida. The deets: The lab simulates a modern grid control room where students and faculty can work to meet the need for sustainable, affordable and reliable energy. | | | | | | 4. Tackling the mysteries of multiple sclerosis |  | | | Illustration: Shoshana Gordon/Axios | | | | A decade of technological and scientific advances is starting to shed light on possible causes, better diagnostics and potential treatments for multiple sclerosis, Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly writes. Why it matters: MS — a central nervous system disease affecting almost 3 million people globally — has baffled doctors since it was discovered over a century and a half ago. The disease can advance silently for years, but then attack myelin, the protective coating around nerve cells, and produce lesions that can cause vision problems, muscle weakness and more. It is unknown why the disease can progress in unpredictable and different ways. - FDA-approved treatments are designed to slow the progress of the disease or try to reverse myelin damage, but often have serious side effects, including possible liver damage, an elevated risk of certain cancers and rendering COVID-19 vaccines less effective.

The latest: Researchers yesterday published a study that found four new autoantigens, or disease-driving immune cells, that could be targeted in both diagnostics and drugs. - Autoantigens "may lie at the core of MS" and could help researchers understand what aspects of the immune system MS is targeting, says study co-author Mattias Bronge, a Ph.D. student at Karolinska Institutet.

- While this hasn't been tested yet, it might be possible to increase the immune system's tolerance for some antigens so the disease's effects are reduced, similarly to what is done in allergy treatments, Bronge says, and those four new identified proteins may help advance this idea.

Yes, but: Scientists must first better understand how "the immune system orchestrates damage to brain cells and what is required for the brain to repair itself better," says Daniel S. Reich, neuroradiologist and senior investigator for NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Between the lines: MS is believed to be caused by a mix of genetic susceptibility, faulty immune systems, and environmental factors. A crucial discovery is the probable link of MS with the Epstein-Barr virus, a common herpes virus that infects almost all people by adulthood and is more well-known as a cause of mononucleosis. Go deeper. |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time |  | | | South American marked gecko (Homonota horrida). Photo: Ignacio Roberto Hernández | | | | One-fifth of the world's reptiles are at risk for extinction (Axios) Leonardo da Vinci's rule for how trees branch was close, but wrong (James Riordon — Science News) How long will your dog live? (Jonathan Amos — BBC) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | Credit: Elliot Hawkes/UC Santa Barbara | | | | A robot is setting records: Engineers have built a device that can jump more than 100 feet high — 100 times its height. The big picture: Existing devices use some of the biological tricks found in insects and other animals, but have been able to jump only so high. - The new design could help robots explore the moon and other areas so far only accessible by flying devices, the engineers report..

How it works: The amount of energy a biological system has to push its body off the ground is limited by how much energy a single stroke of their muscles can produce, says Elliot Hawkes, an engineering professor at University of California Santa Barbara and one of the authors of the study published this week. - In insects, a tiny biomechanical "spring" stores the smaller amounts of energy produced by their relatively heavier muscles.

- But, like wind-up cars, the new engineered jumpers "use motors that ratchet or rotate to take many strokes, multiplying the amount of energy they can store in their spring," he says.

- The springs in the robot are large and the motors small and lighter weight — the opposite of animals. And the robot's "legs" fold up as it launches.

"Incredibly, it goes from being perfectly still to 60 mph in 9 milliseconds. That's an acceleration of 315 g!" Hawkes says. - But, but, but ... "Biological jumpers do many other things way better and are way more robust. They can run, walk, turn, spin, climb in all sorts of environments."

The big picture: Biology can inspire successful engineered designs, but the study shows "an ideal solution in biology is not always ideal in engineering," he says. |     | | | | | | A message from University of Central Florida | | How to secure the energy grid of the future | | |  | | | | UCF's Microgrid Control Lab enables students and faculty to test real-life grid control operations, including finding ways to optimize and secure the grid of the future. See how UCF is investing in future engineers and the nation's infrastructure. | | | | Thanks to Andrew and Eileen for contributing to this week's newsletter, to Shoshana Gordon and Aïda Amer on the Axios Visuals team, and to Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing this edition. |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments