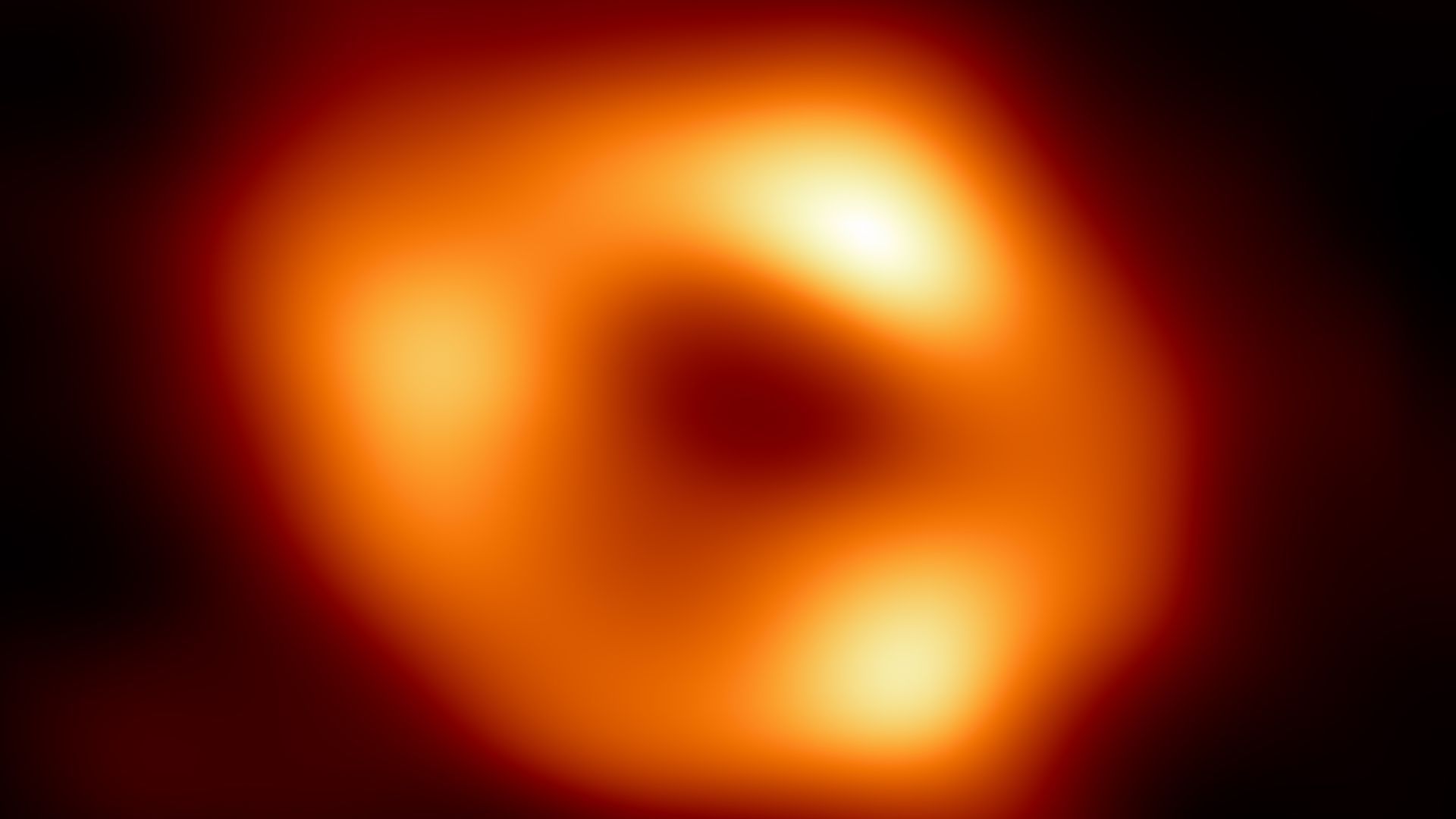

| | | | | | | Presented By University of Central Florida | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · May 12, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's edition is 1,754 words, about a 6.5-minute read. | | | | | | 1 very big thing: A portrait of the Milky Way's massive black hole |  | | | The first image of Sagittarius A*, or Sgr A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. Source: Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration | | | | The first image of the black hole at the center of the Milky Way has been captured, astronomers announced today. Why it matters: The "historic breakthrough" offers an unprecedented look at the extreme object driving the evolution of our galaxy. Driving the news: Astronomers imaged Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*) using the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT). - Most galaxies are thought to have a supermassive black hole at their center.

- Light can't escape a black hole but hot plasma swirling around it emits short radio waves that radio telescopes can pick up. In the image, the gas silhouettes the black hole itself.

What they're saying: "For decades, astronomers have wondered what lies at the heart of our galaxy, pulling stars into tight orbits through its immense gravity," Michael Johnson, an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics, said in a news release. - "With the EHT image, we have zoomed in a thousand times closer than these orbits, where the gravity grows a million times stronger. At this close range, the black hole accelerates matter to close to the speed of light and bends the paths of photons in the warped spacetime," Johnson added.

The very big picture: Black holes can tear apart and devour nearby stars, generate massive bursts of gamma-ray energy that shape the galaxies around them and, recent evidence suggests, ignite the formation of new stars. - Einstein's theory of general relativity predicts the existence of black holes — and his century-old rule consistently passes cosmic tests near and far.

- But scientists hope these massive, dense objects may also reveal instances where general relativity doesn't hold. These important limits could point them to conditions that require a new physics to describe.

- Any new physical laws, together with general relativity and Newtonian physics, could give us a more complete view of the physics of the universe.

|     | | | | | | 2. The details | | Sgr A* is less than 26,000 light years from Earth — far closer than the supermassive black hole at the center of galaxy Messier 87, the first imaged by EHT. - At about 4 million times the mass of the Sun, it is also far smaller than the 6.5 billion solar masses of M87* suggested by the EHT measurements.

- M87* is one of the biggest black holes in the universe, while Sgr A* is of a more common size, Johnson said in a news conference.

The "gentle giant in the center of our galaxy" is consuming very little matter compared to others but its temperature and magnetic fields are quite high, astronomer Feryal Özel of the University of Arizona said. - The diameter of the shadow was determined to within 10% and is consistent to indirect observations and that predicted by general relativity, Johnson said.

- The results were published today in a series of papers in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

How it works: The EHT is an international collaboration that uses data from ground-based telescopes in Hawai'i, Spain, the South Pole, Chile and other locations. - Working in pairs, eight observatories formed an Earth-sized telescope capable of measuring the interference of millimeter radio waves from hot plasma near the edge of black holes — a technique called very-long-base interferometry (VLBI). The data was collected over five nights in April 2017, alongside data from M87.*

- But Sgr A* is fast-changing — on the order of minutes rather than the changes seen in M87* over weeks — and needed to be imaged quickly. The international team of more than 300 scientists tackled that challenge by creating more than 5 million images in total and averaging them together to reveal the features of the ring.

- Comparing the data to computer simulations of the black hole suggests it is rotating, Johnson said at the news conference.

The intrigue: The team didn't release all of the data they collected. On one night, Sgr A* was active and erupting, sending bursts of energy seen in infrared and X-ray wavelengths, theoretical astrophysicist Ramesh Narayan of Harvard University told Axios. - By analyzing eruption data, they may get clues about how the plasma near the black hole is being heated — possibly by flares.

General relativity didn't crack in the results reported today. - If it is going to break down, it would likely be seen in data from the LIGO experiments, says Matthew Strassler, a theoretical physicist at Harvard who isn't involved in EHT. Those experiments detect gravitational wave signals from colliding black holes and neutron stars.

- But as the black hole imaging measurements become sharper, there may be opportunities to ask new questions, he added.

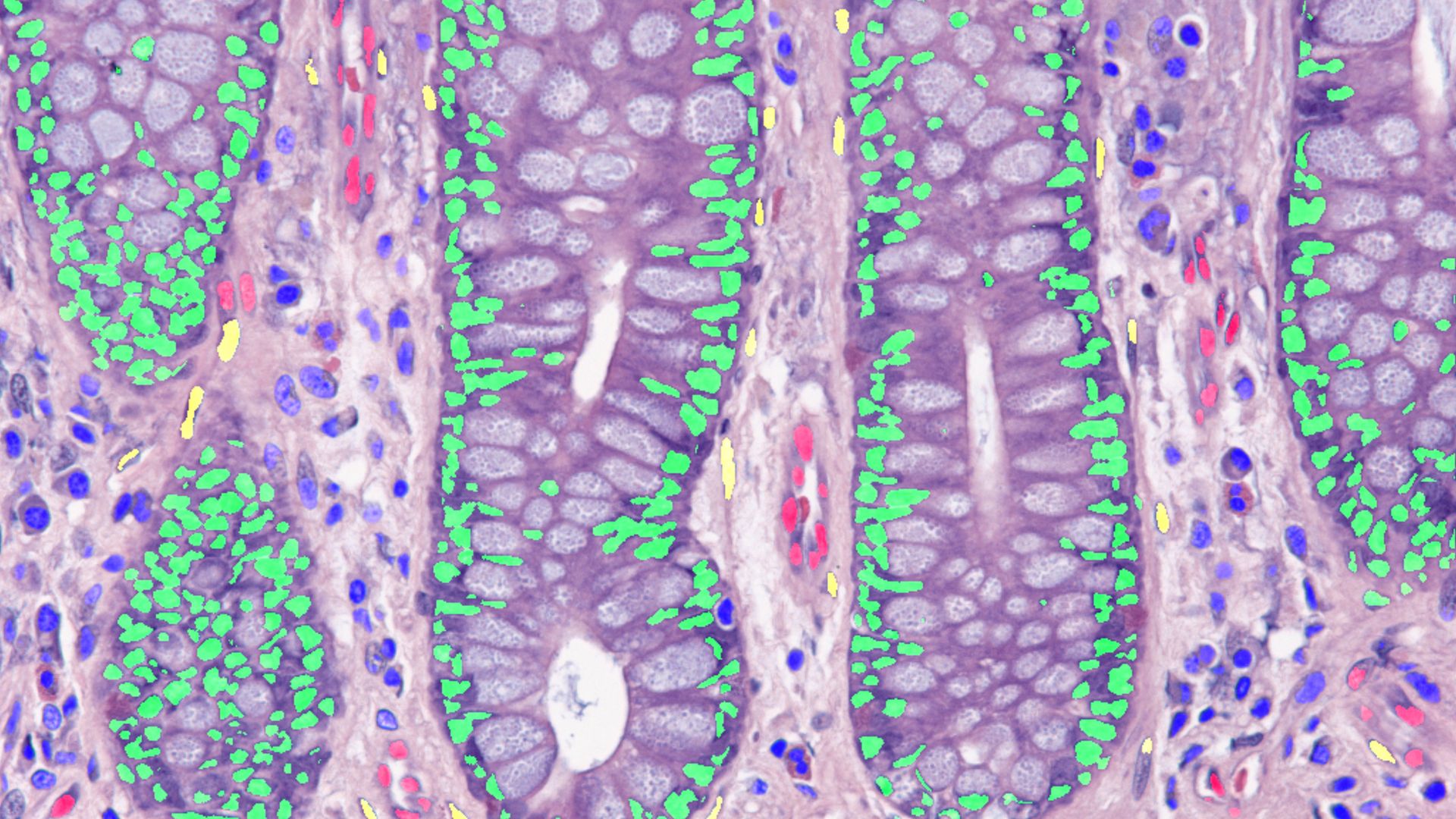

What's next: Astronomers hope to create videos of a black hole by the end of the decade and to incorporate data from space-based telescopes that don't have to contend with interference from Earth's atmosphere. |     | | | | | | 3. Catch up quick on COVID |  Data credit: Our World in Data, History.com, Axios research; Graphic: Kavya Beheraj/Axios The U.S. has reached 1 million reported deaths as COVID fades from the headlines, a team of Axios visual and health journalists writes. Explore their graphic visualizing the scale of loss. COVID or allergies? Mariana Lenharo at Scientific American looks at some ways to help tell them apart. "Scientists are studying whether long COVID could be linked to viral fragments found in the body months after initial infection," Heidi Ledford reports for Nature. |     | | | | | | A message from University of Central Florida | | America's space university | | |  | | | | The University of Central Florida (UCF) helps discover and shape humankind's footprint in space. The impact: - UCF is involved in 674 NASA projects.

- 29% of Kennedy Space Center employees are UCF alumni.

- Eight UCF experiments have been sent to space since 2019.

Discover UCF's space discoveries. | | | | | | 4. Congress urged to ease immigration for foreign science talent |  | | | A technician pushes a cart of semiconductor wafers at the Applied Materials Inc. facility in Santa Clara, Calif. Photo: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty Images | | | | More than four dozen former national security leaders are calling on Congress to exempt international advanced technical degree holders from green card caps in a bid to maintain U.S. science and tech leadership, especially over China, according to a copy of a letter viewed by Axios. Why it matters: The breadth of signatories suggests widespread concern about China's rise could bolster bipartisan support for change in one corner of the otherwise politically charged issue of immigration policy, Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian and I write. Context: China competition bills passed in the last year by the House and Senate seek to pour money into the National Science Foundation and other federal research agencies. They also seek to motivate high-tech companies, especially those that manufacture semiconductors, to build facilities in the U.S. - The America COMPETES Act passed by the Democrat-led House includes a provision to exempt foreign-born science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) doctoral degree recipients from green card caps.

- The exemption would be offered whether their degree is from a U.S. or foreign institution.

- Current U.S. immigration law limits the number of green cards issued per country, and people from populous countries like India and China are disproportionately affected.

What's happening: The Bipartisan Innovation Act Conference Committee is expected to begin this month to try to reconcile the House and Senate bills. - Several Republican senators, including Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) and Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) have said they're open to keeping the green card provision in final legislation.

- The letter, dated May 9, is addressed to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy and the conference committee.

- Signatories include former Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff, former Secretary of Energy Steve Chu, former deputy undersecretary of defense for intelligence and security Kari Bingen and 46 others.

What they're saying: "China is the most significant technological and geopolitical competitor our country has faced in recent times. With the world's best STEM talent on its side, it will be very hard for America to lose. Without it, it will be very hard for America to win." - Keeping the House bill provision or some version of it would remove "the self-inflicted drag that immigration bottlenecks impose on American competitiveness," the letter says.

Between the lines: "People are recognizing very critical national security goals can't be achieved unless international STEM talent has a way to come and stay in the U.S.," says Remco Zwetsloot, who researches STEM immigration and U.S.-China technological competitiveness at CSIS. Read the rest. |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time |  | | | Different types of cells that make up intestinal glands are shown on an image of stained tissue. Credit: Pranathi Vemuri/Chan Zuckerberg Biohub and Serena Tan/Stanford | | | | Publication of the "Google Maps" of human cells is a milestone. A pioneer of the project explains why (Megan Molteni — STAT) The race to produce green steel (Marcello Rossi — Undark) What attracts mosquitoes to humans (Sophie Fessl — The Scientist) Spinal fluid of young mice sharpened memories of older rodents (Benjamin Mueller — NYT) |     | | | | | | 6. Something wondrous |  | | | An Arabidopsis plant grown in lunar soil for about two weeks. Photo: Tyler Jones/UF/IFAS | | | | Earthly plants have been grown in lunar soil for the first time, researchers report today. Why it matters: Just as on Earth, plants would likely play a key role in supporting humans living and working in space for an extended period. - "When we go to stay somewhere, we always take our agriculture with us ... and that will be incredibly important on the Moon," Robert Ferl, one of the three study co-authors from the University of Florida, said in a news briefing, adding that plants will provide food, purify the air and help to produce clean water.

- "The idea of bringing lunar soil into a lunar greenhouse is the stuff of exploration dreams."

How they did it: The scientists grew Arabidopsis thaliana — the fruit fly or mouse of plant biology — in soil returned from the Apollo 11, Apollo 12 and Apollo 17 missions. - The fine material is collected from the outermost layer of the surface of the Moon.

- It lacks carbon and nutrients plants need, including nitrogen and phosphorus, and the pieces of the fine material are sharp and angular, co-author Stephen Elardo said. There are tiny glass fragments in the soil that contain gases and iron.

What they found: The plants can grow in lunar soil but "respond as if they're growing in a stressful situation," co-author Anna-Lisa Paul said in the briefing. - The plants germinated normally then began to grow more slowly and had shorter roots than those grown in a control material of volcanic ash that simulates lunar soil. Some of the plants were reddish black — an indicator they were stressed.

- The researchers then analyzed the expression of genes in plants grown in lunar soil and found they were similar to those when plants are stressed by salt or metals in soil, they report today in the journal Communications Biology.

Of note: Plants grown in Apollo 11 soil— which was exposed on the surface for a longer period of time — fared the worst of the plants grown in lunar soil from the three different missions. - That's the most "mature" material with the longest exposure to damaging cosmic rays and solar winds, the researchers wrote.

- Lunar soil would have to be further characterized and optimized before it could be routinely used to grow plants, they wrote.

The bottom line: "From the standpoint of someone who doesn't study plants, but studies geology, it's pretty incredible to me that the plant is so hearty and so adaptable that it can still grow in this harsh environment," Elardo said. |     | | | | | | A message from University of Central Florida | | The return to the Moon | | |  | | | | The University of Central Florida has more than a dozen research projects aimed at returning the U.S. to the Moon. The deets: The projects help the future of launching and landing spacecraft, mining fuel, and protecting astronauts and their equipment from lunar dust. Explore UCF space research. | | | | Big thanks to Laurin Whitney-Gottbrath for edits and to Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing this edition. |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments