| | | | | | | Presented By 3M | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Jun 23, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,626 words, about a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: The immune system's clock |  | | | Illustration: Annelise Capossela/Axios | | | | The body's internal clock affects the immune system in ways scientists in the burgeoning field of circadian immunology are beginning to unwind. Why it matters: Leveraging the circadian clock's effects on the immune system could help to improve the effectiveness of some treatments for a range of diseases and conditions, a new book and scientific review suggest. How it works: The body's central clock, or suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), is a collection of about 20,000 neurons in the brain that receives signals from the eye when it detects light or other environmental cues from the body. - The signals trigger the clock's components — a network of genes that regulate the production of different proteins in the neurons. (Other cells in the SCN also tamp down the neurons' activity). The amounts of those proteins in the cell oscillate over 24 hours, setting the clock's pace.

- The central timekeeper then coordinates other clocks in the body and sets the rhythm for regulating body temperature, sleep schedule, the release of hormones and a slew of other biological processes.

- "Without this precise regulation by an internal clock, our entire biology would be in chaos," writes Russell Foster, a professor of circadian neuroscience at the University of Oxford, in his new book, "Life Time" about the science of the body clock and its connection to health.

The immune system is also under the control of the clock: The functions of different immune cells have been found to oscillate over the course of a day. - The circadian clock "synchronizes the whole body to the outside world but we don't know exactly how an immune cell sees it," says Christoph Scheiermann, an immunologist at the University of Geneva and a co-author of a recent review about the circadian immune system.

What's new: Studies suggest the time of day that a vaccine is given can change the immune system's response to it. - The immune response to vaccination against influenza or tuberculosis in two different studies tended to be greater in people vaccinated in the morning compared to those who received shots later in the day.

- Two other small studies found the immune response to COVID-19 vaccination depended on the time of day — but the optimal timing depended on which vaccine was administered.

- Earlier work found the timing of when medications or treatments for some cancers, asthma, heartburn and other conditions are given can influence their effectiveness.

But, but, but ... The variations between someone's immune system and their body's rhythms mean the best time for a treatment could vary from one person to the next. - The rhythms are generally the same for most individuals and it's likely recommendations can be made for most of the population most of the time, says Jacqueline Kimmey, a professor of microbiology at UC Santa Cruz.

- But making recommendations for individuals isn't possible "until we have better ways of measuring what 'time' someone's body says it is, and more specific knowledge on what 'time' we should be doing something," she says.

- There can be differences due to genetics, behavior and environment. "Morning" in the body of a night shift worker may be 3pm so if they go for a vaccine at 8am, they may not benefit from the effects of time, says John Hogenesch, a professor of human genetics and director of the Center for Circadian Medicine at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

- Altering the time may also not be practical for certain therapies like cancer treatments that hospitals have a limited capacity to administer at particular times.

|     | | | | | | 2. Part 2: While you are sleeping | | Scientists have known about immune rhythms for decades but new tools are allowing them to better understand the cues and components of the body's clocks. - Immune rhythms coordinate and balance the immune system's different responses over the course of the day.

- Parts of the adaptive immune system — which learns to target pathogens through vaccination or infection — are throttled against new invaders during the day.

- At other times, the responses are turned down so the immune system doesn't turn on itself and trigger an autoimmune disease.

The innate immune system, a more immediate and blanket response to pathogens is also controlled by the clock. - In a study published last week, researchers found when mice and marmosets rested, skin cells produced proteins that protected the animals from staph infection and jump-started the innate immune response.

The impact: Sleep disruptions can alter the body's clock and throw off the immune defense system, making it more susceptible to disease. - It can also push the body to produce stress hormones, which suppress the immune system.

- Some viruses, like influenza, also disrupt the immune system's circadian rhythm, blunting the immune response and enhancing the virus' own replication.

- The malaria parasite reproduces in sync with the circadian clock and releases a flood of parasites that overwhelms the immune system at night when its guard isn't as high, Foster writes.

When people are being infected or treated is "a huge variable we're not paying attention to," Kimmey says. - Knowing that the adaptive immune system is not as turned up at night compared to the day, employers can take measures to better protect shift workers — like providing protective equipment for frontline medical workers caring for people with a virus, Foster says.

|     | | | | | | 3. Tracking disease outbreaks from space |  | | | Illustration: Allie Carl/Axios | | | | Scientists are tracking diseases from space and getting a new view of human health, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: The proliferation of easy-to-use, relatively cheap and more comprehensive satellite data is allowing researchers to get a holistic view of what's happening on Earth during disease outbreaks and possibly learn how to predict the next one. How it works: By keeping an eye from above on changes to vegetation and other ecosystem factors that can lead to outbreaks, researchers are starting to piece together correlations between habitat loss and urbanization, among other factors, and infectious disease. - Remote sensing data has been used to find that a major predictor of monkeypox cases in humans was the proximity of people to dense forests and habitats where rope squirrels that can carry the virus lived.

- If those areas are closely monitored, it could help people on the ground figure out which areas are at the highest risk for infection.

- Habitat loss particularly impacts predators, leaving a plethora of infected prey that could circulate the disease or transmit it to other species.

What to watch: Space data could one day be used to aid in a range of public health responses to certain diseases — from monitoring to mitigation. - If health officials on the ground know when there's a high risk for a given outbreak, then they can put measures in place to help prevent it, according to Farhan Asrar, a clinician and researcher at the University of Toronto.

- "Once things happen, can we use those [satellite] images to prepare an ideal situation to set up offices and support facilities," Asrar said.

Where it stands: Satellites have already been used to learn more about the source of the Ebola virus, track an outbreak of Rift Valley fever and aid in the response to Zika. - During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, satellite companies like Planet were able to track economic impacts of the virus from orbit, keeping an eye on empty parking lots and traffic.

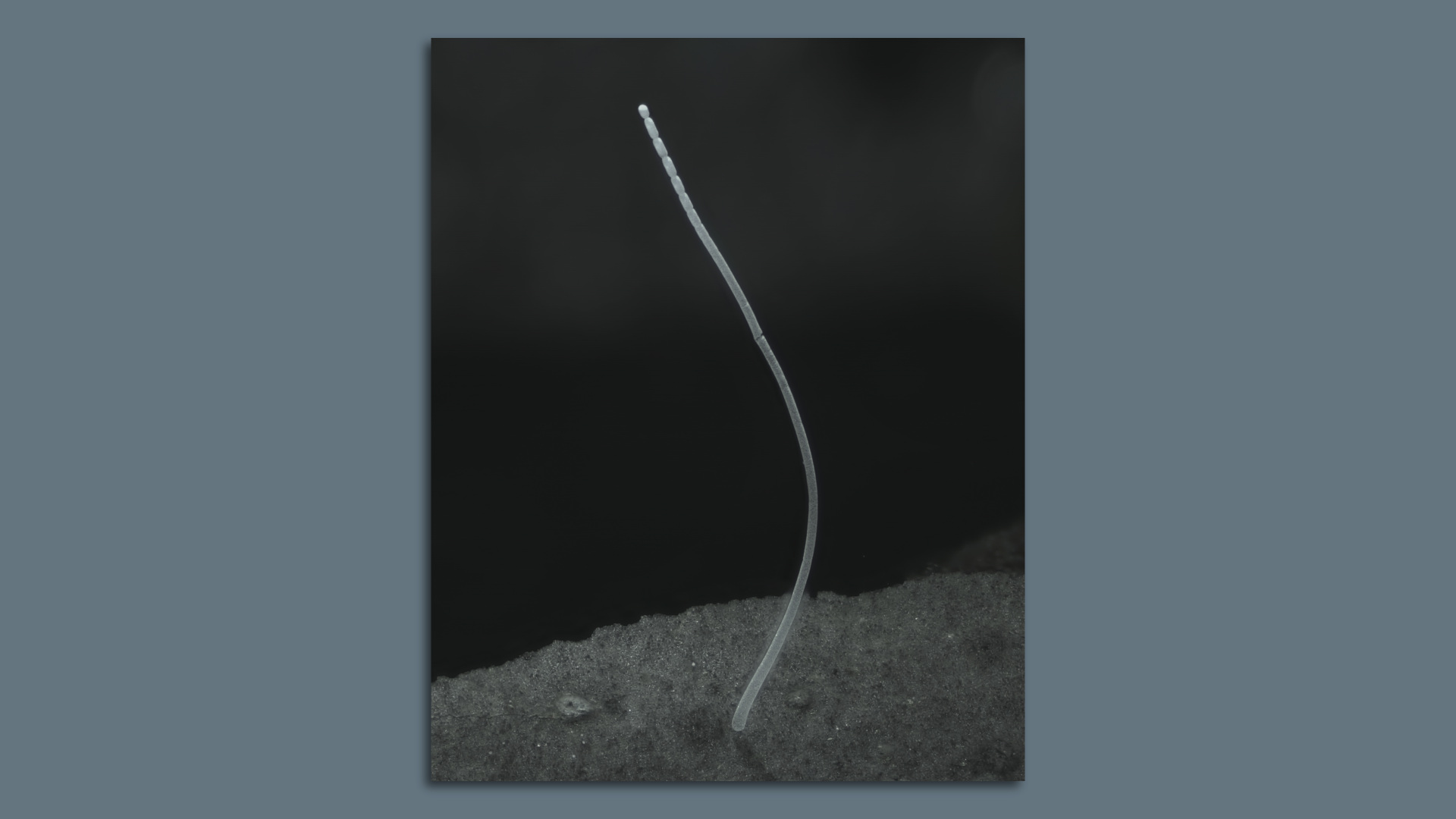

Go deeper. |     | | | | | | A message from 3M | | New survey findings show barriers to STEM persist | | |  | | | | Americans are more likely to think barriers exist to accessing a strong STEM education, compared to last year. The proof: 69% of respondents of the 2022 State of Science Index say underrepresented minorities often don't have equal access to a strong STEM education. How science companies can help. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | Female scientists are less likely to get research credit (Tina Reed — Axios) Monkeypox in Africa: the science the world ignored (Max Kozlov — Nature) An otherwise quiet galaxy in the early universe is spewing star stuff (Liz Kruesi — Science News) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | Thiomargarita magnifica. Photo: Jean-Marie Volland/Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory | | | | A single cell the size of a human eyelash is now the world's largest known bacteria, scientists report this week. The big picture: The discovery challenges theories about how big bacteria can be. - "It would be like a human encountering another human as tall as Mount Everest," Jean-Marie Volland, a researcher at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) and a co-author of the new study said in a news briefing.

Details: Thiomargarita magnifica is 50 times larger than other known giant bacteria and can be seen with the naked eye. - Marine biologist Olivier Gros of the Université des Antilles in Guadeloupe discovered the nearly centimeter-long bacterium attached to sunken mangrove leaves. It was first reported in a preprint paper earlier this year and is described in more detail in a paper published today in the journal Science.

- The bacterium has more than 500,000 copies of its genome (which has three times as many genes as most other bacteria) in a single cell. With six terabytes of DNA, the bacterium stores 1,000 times more DNA than a human cell, said co-author Tanja Woyke of LBNL.

- Unlike other bacteria in which DNA floats around the cell, the bacterium's DNA is encapsulated in compartments in the cells — an unusual degree of complexity for bacteria.

- The researchers suggest the DNA is compartmentalized because the bacterium has to have multiple copies of its genome to produce the proteins it needs throughout its giant structure.

The intrigue: The giant cells aren't fragile. - It is "actually quite puzzling to realize that a single bacterium can be so strong and hold its shape like this," Volland said, adding "it is probably the first opportunity we have to play with tweezers with a single bacterium."

- It's unclear why the bacterium is big. One possibility is that it is bigger than its predators and can escape them.

What they're saying: The complex bacterium isn't the missing link between single-celled prokaryotes and multicellular eukaryotes, the researchers said. - "But it has come close to achieving similar kinds of complexity as you would see in eukaryotic cells," co-author Shailesh Date of the Laboratory for Research in Complex Systems said.

- "The project has opened our eyes to the unexplored microbial diversity that exists. Who knows what interesting things we are yet to discover?"

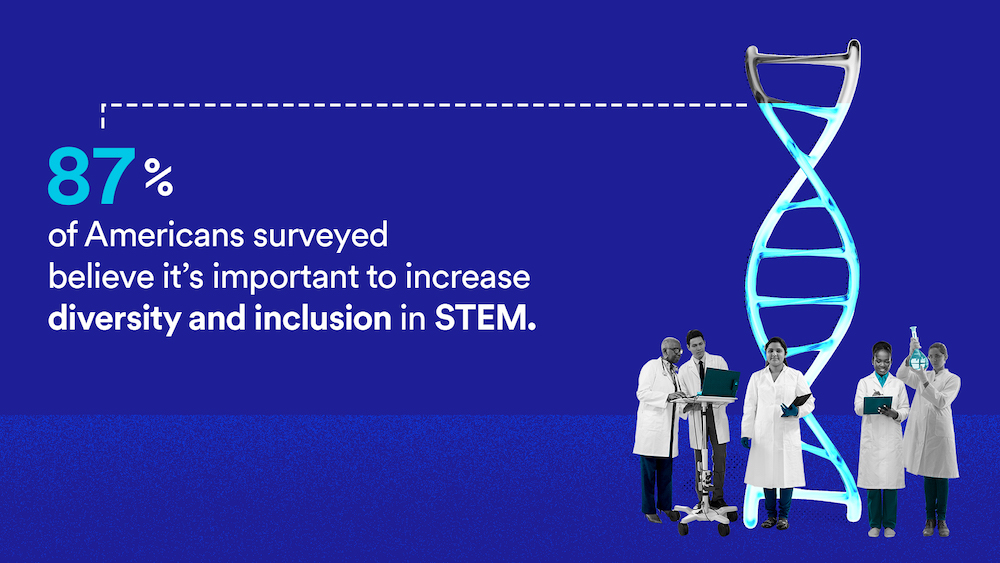

|     | | | | | | A message from 3M | | The STEM workforce gap | | |  | | | | Global survey findings from 3M and Ipsos show many Americans aren't seeing representation gaps that clearly exist in the STEM workforce. The proof: Only 57% of Americans believe a gender gap exists in the STEM workforce, 56% believe a racial gap exists and 40% believe an LGBTQ+ gap exists. Learn more. | | | | Big thanks to Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath and Carolyn DiPaolo for editing this week's newsletter. |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments