| | | | | | | Presented By University of Central Florida | | | | Axios Space | | By Miriam Kramer · Jun 07, 2022 | | Thanks for reading Axios Space. At 1,373 words, this newsletter is about a 5-minute read. - Please send your tips, questions and ice giant facts to miriam.kramer@axios.com, or if you received this as an email, just hit reply.

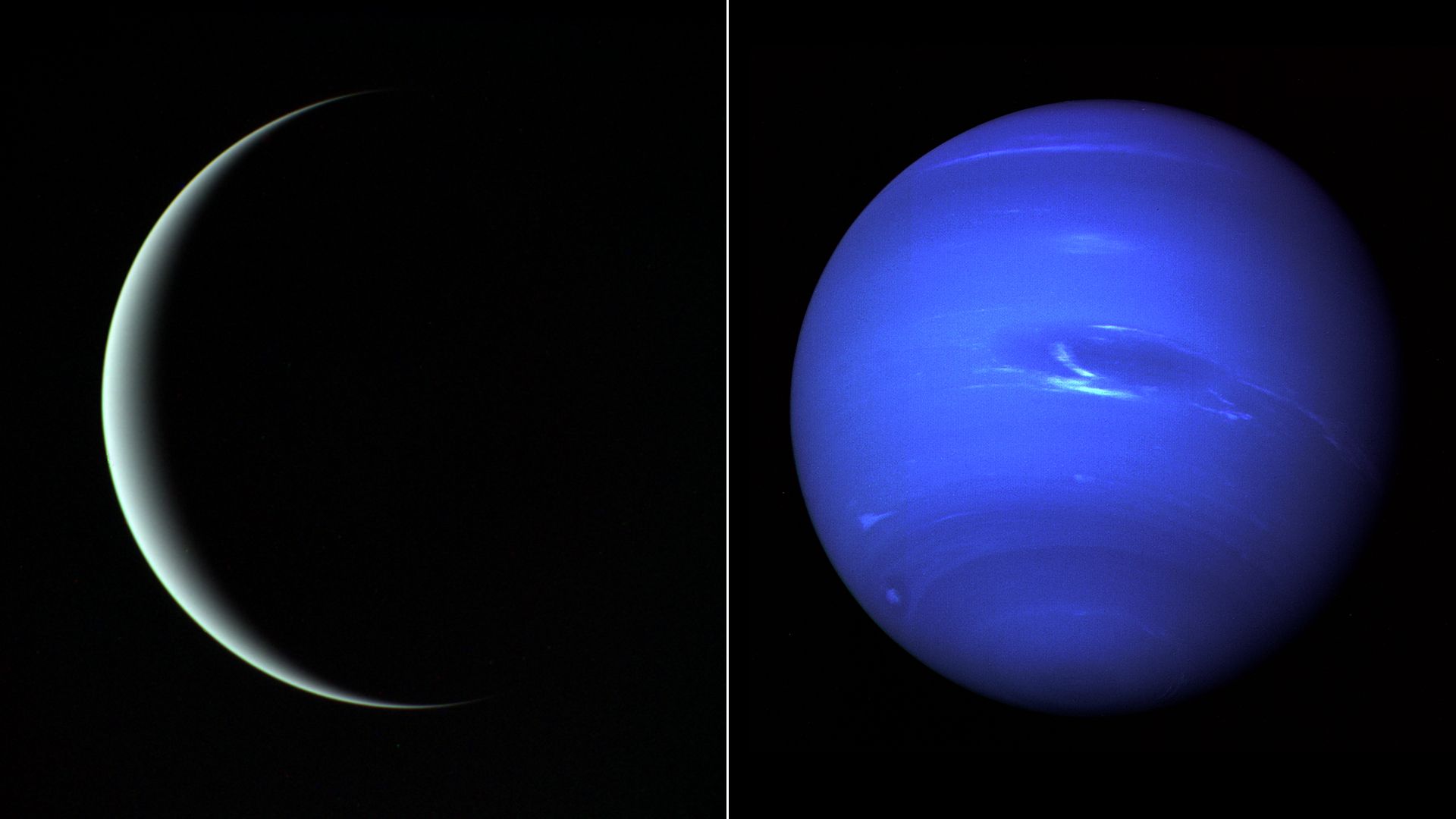

| | | | | | 1 big thing: The growing mysteries at the edge of the solar system |  | | | Uranus, left, and Neptune. Photos: NASA/JPL | | | | Unanswered questions are mounting about Uranus and Neptune. Why it matters: The two cold, distant worlds could hold the key to figuring out why Earth ended up being so hospitable to human life — and understanding similar worlds beyond our solar system. - "The more we learn, the more we realize how little we actually did know about these two amazing planets," Kathleen Mandt, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins' Applied Physics Lab, told me.

- Uranus and Neptune are the two major planets in the solar system that haven't been visited by dedicated missions, leaving major holes in how scientists understand the solar system.

- For years, planetary scientists have called on NASA and other funding agencies to make these worlds a priority for future missions, and now these planets could be explored in the not-too-distant future.

What's happening: A study published last month used data from the Hubble Telescope and other observatories to try to answer the question of why these icy giants appear to be different colors. - The researchers found Uranus has a thicker methane haze layer in the middle of its atmosphere than Neptune has, giving it a distinctive greenish hue.

- "There's still an awful lot of uncertainty," Oxford University's Patrick Irwin, an author of the new study, told the New York Times. "We don't really know what the particles are made of. The only way to really know what's going on is to drop a probe into these deep atmospheres."

The big question: How — and where — did both of these planets form? An answer could help scientists understand the origins of Earth's life-sustaining water. - It's still not clear where Uranus and Neptune formed in the disk of gas and dust surrounding the Sun during the early moments of the solar system.

- If Uranus and Neptune migrated through the early solar system along with Jupiter and Saturn, which underwent their own complicated dance, the worlds could have flung comets and water-laden asteroids toward Earth, delivering water to our planet.

- "We don't understand the interior structure of these planets," Mandt said. "We don't know how they formed with so much less hydrogen and so much more of the heavier elements than Jupiter and Saturn."

The intrigue: Unlocking the mysteries of the ice giants will also allow scientists to learn more about worlds far beyond our own solar system. - Many exoplanets found by planet-searching missions appear to have a similar mass and radius to Uranus and Neptune.

- But because scientists know very little about the structures of the two ice giants, it's difficult to understand — or even guess at — the nature of those far more distant worlds.

- "There are 1,500 planets that we're trying to categorize without knowing how our own two work," NASA planetary scientist Amy Simon told me.

What to watch: So far, the only mission to visit Neptune and Uranus from close range was a quick flyby of the worlds made by Voyager 2 in the 1980s, but that could change in the relatively near future. - A major report from the scientific community laying out the priorities for planetary research in the coming decade put a Uranus mission at the top of the list for NASA.

Yes, but: A dedicated mission to Neptune may need to wait a little longer. - It's not that Uranus is more interesting than Neptune, experts say. Prioritizing Uranus is actually a more practical choice — the planet is much closer, and it's easier to get a spacecraft out there using current technology.

- "Just getting out to either one is difficult, but Neptune is really, really hard," Simon said.

|     | | | | | | 2. NASA needs new spacesuits |  | | | Artist's illustration of an astronaut on the Moon. Image: NASA | | | | NASA has inked a deal with two private companies to build spacesuits the space agency can use on the Moon and in orbit. Why it matters: The suits will be key to the space agency's plans to send people to the Moon with its Artemis program. Passing off their development to private companies will help to further commercialize yet another aspect of human spaceflight. What's happening: NASA announced last week that Axiom Space and Collins Aerospace have been awarded contracts to create next-generation spacesuits to help replace the agency's aging ones. - The total value of the award is $3.5 billion, but NASA declined to break that figure down by company.

- Both companies are also using their own funds to develop their spacesuits, and Collins and Axiom will own the spacesuits for their own uses and customers other than NASA.

- The suits will also be designed to fit a wide range of bodies from a 5th percentile woman to a 95th percentile man. (NASA has faced criticism recently for its current suits that are more limited in size.)

- The spacesuits are expected to be ready for the first crewed Artemis landing on the Moon, currently scheduled for 2025.

Between the lines: This kind of partnership is designed to be mutually beneficial for NASA and the companies it's partnering with. - Axiom has long been focused on building a commercial space station, and CEO Michael Suffredini said because of that, the company has a need for a spacesuit.

- "We have a number of customers that already would like to do a spacewalk, and we had planned to build a suit as part of our program," Suffredini said during a press conference last week.

The intrigue: A report last year called out NASA's own years-long development of new spacesuits as a major limiting factor in sending people back to the Moon's surface by 2024 —which was the expected landing date at the time. - In November, the agency switched its target landing to 2025, and now the spacesuits are in the hands of these private companies.

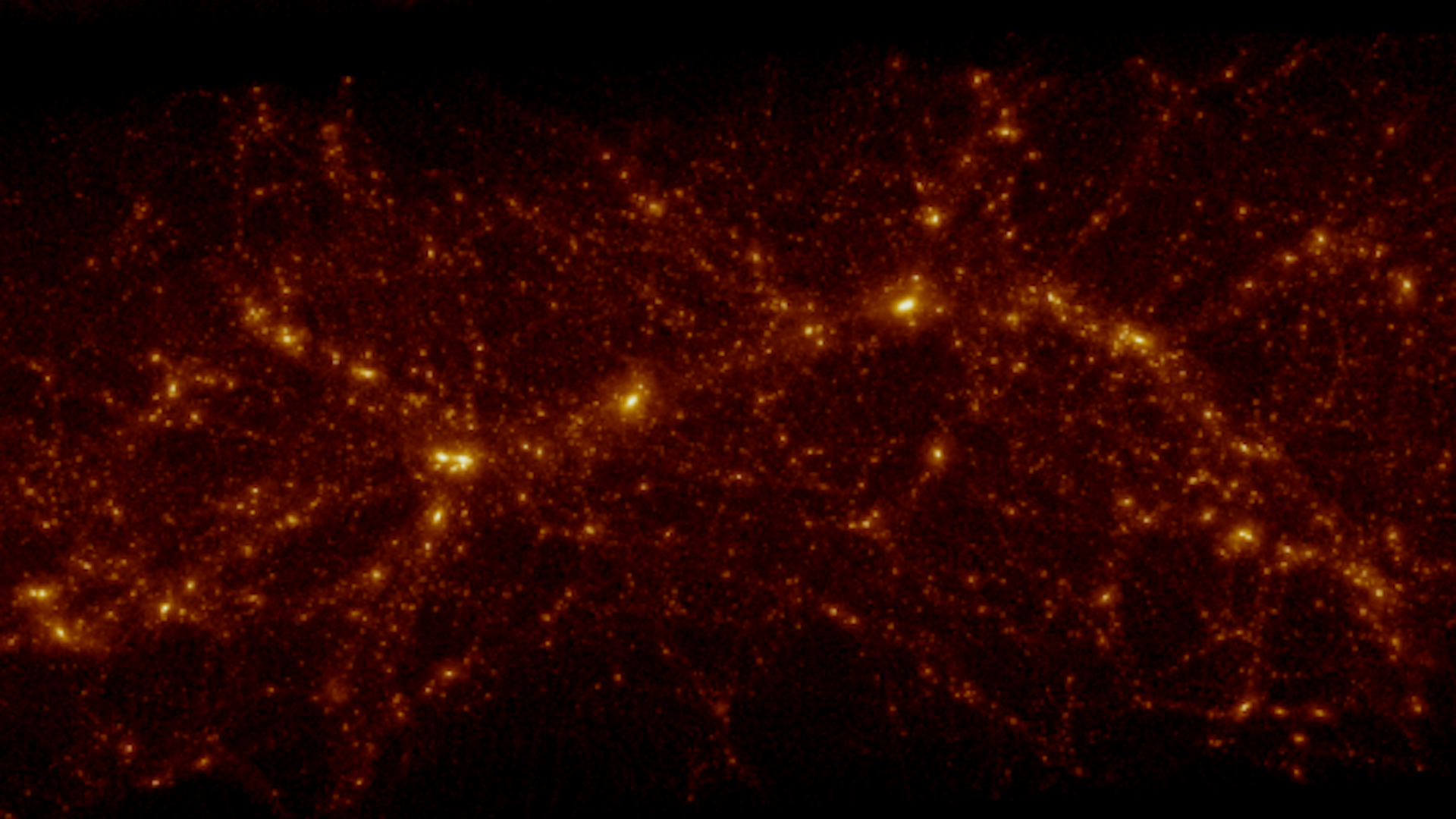

|     | | | | | | 3. Simulating the universe |  | | | A simulation of the universe. Image: Ata et al/Kavli | | | | Scientists have created models that mimic the lives and structures of huge groupings of galaxies seen in the early universe, 11 billion years ago, a new study reports. Why it matters: By having simulations that show the machinations of these galaxy clusters on a large scale, scientists will be able to test fundamental aspects of our understanding of the nature and physics of the universe. What they found: The new study, published in the journal Nature Astronomy, simulated protoclusters of galaxies — the predecessors to current galaxy clusters — to see if they could reproduce what's currently observed. - "We wanted to try developing a full simulation of the real distant universe to see how structures started out and how they ended," Metin Ata of the Kavli Institute and an author of the study said in a statement.

- The team of researchers essentially took images of distant galaxies and used the simulation to speed up their evolution to see how galaxy clusters would form.

- This marks the first time a simulation has successfully re-created these detailed, galaxy cluster life cycles, according to the study.

The big picture: These types of simulations can also be used to put the standard model of cosmology to the test, according to the researchers behind the study. - "By predicting the final mass and final distribution of structures in a given space, researchers could unveil previously undetected discrepancies in our current understanding of the universe," a press release says.

- The simulations even show the Hyperion proto-supercluster — the largest known and with 5,000 times the mass of our galaxy — will collapse, stretching into a 300 million light-year-long thread of galaxies and matter one day.

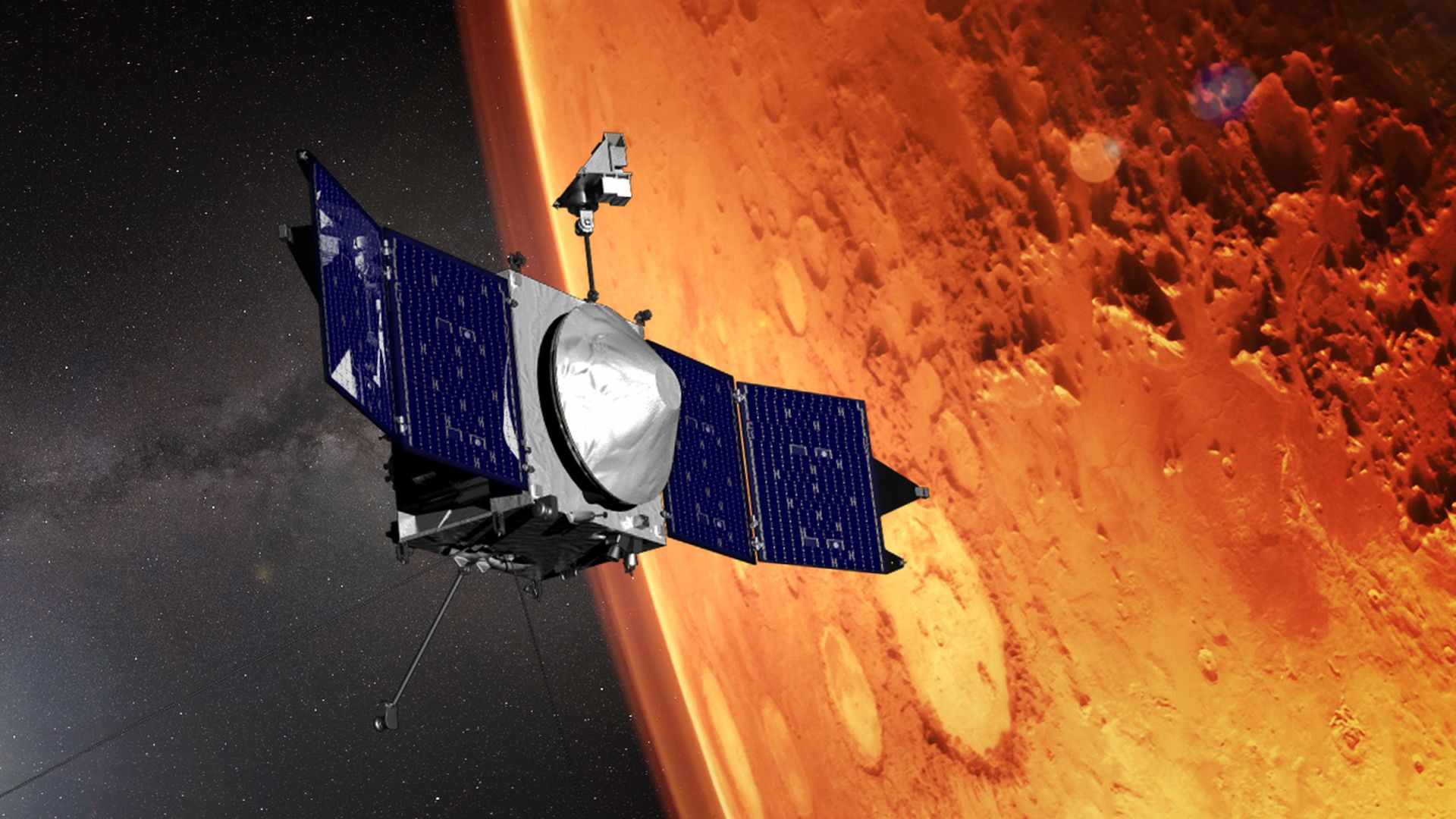

|     | | | | | | A message from University of Central Florida | | Can Martian simulant soil save $7B? | | |  | | | | NASA says a mission to retrieve regolith may cost $7B. UCF's Exolith Lab makes simulant Martian soil with data from the Mars rover here on Earth for $35 per kg. While not from distant planets, dirt from the Exolith Lab is used to test rovers and impacts on sensitive instruments for future missions. | | | | | | 4. Out of this world reading list |  | | | Image: NASA | | | | A newfound, oddly slow pulsar shouldn't emit radio waves — yet it does (Liz Kruesi, Science News) NRO contracts will have long-term ripple effects on satellite imagery industry (Sandra Erwin, SpaceNews) SpaceX cargo mission grounded to investigate possible fuel leak (Stephen Clark, Spaceflight Now) NASA orbiter around Mars faced "existential threat" (Axios) |     | | | | | | 5. Weekly dose of awe: A shooting star |  | | | Photo: NASA | | | | Not all shooting stars are little pieces of dust or rock. Sometimes, a piece of human-made material can put on a truly spectacular show. - This particular shooting star was created by a Russian cargo spacecraft plunging through Earth's atmosphere.

- Crew members on the International Space Station were lucky enough to catch this view of the spacecraft as it disintegrated, leaving a plasma trail as it went.

- The Progress vehicle burned up harmlessly above the Pacific Ocean on June 1.

|     | | | | | | A message from University of Central Florida | | Why are space agencies around the world buying dirt from UCF? | | |  | | | | The University of Central Florida makes Martian, lunar and asteroid simulants for scientists worldwide to test equipment that will explore other worlds. The deets: From how dirt affects their equipment to testing if colonists can grow food, UCF's dirt helps ensure successful future missions. | | | | Big thanks to Alison Snyder, Sam Baker and Sheryl Miller for editing this week's edition. If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe. 🌎 |  | It's called Smart Brevity®. Over 200 orgs use it — in a tool called Axios HQ — to drive productivity with clearer workplace communications. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters. If you're interested in advertising, learn more here.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments