| | | | | | | Presented By the University of Central Florida | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · May 11, 2023 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,579 words, about a 6-minute read. - I'm deeply moved by the emails I received from so many of you last week. Thank you for your supportive words and for sharing your personal stories with me.

- If you're in Houston, join Axios' Bob Gee and Shafaq Patel on Tuesday, May 16, at 8am CT for an event examining ways to expand the local STEM workforce. Register here to attend.

- Send your feedback and ideas to me at alison@axios.com.

| | | | | | 1 big thing: The cosmic constant conflict |  | | | Illustration: Natalie Peeples/Axios | | | | New observations and sharper tools are fueling the debate over a long-sought measurement of how fast the universe is expanding, Axios' Miriam Kramer and I write. Why it matters: A resolution would determine whether scientists' model of the universe is broken or if it's missing something — and would answer key questions about the age, size and history of the universe. Where it stands: For more than 100 years, scientists have tried to measure just how fast the universe is expanding, a key measurement known as the Hubble Constant. - Cosmologists who study changes in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) — an imprint of radiation left on the universe just after the Big Bang — are circling around a measurement of 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

- Others who have used the brightnesses of certain stars to gauge the distance to them are finding the constant's value to be about 74 kilometers per second per megaparsec. Theirs is a measurement of events and features of a more mature universe, many of which were captured by the Hubble Space Telescope.

The big picture: These measurements from both the early and the late universe are very precise. - One or the other could have a problem that is "not yet diagnosed," says Patrick Kelly, a professor of astronomy at the University of Minnesota. It could be a problem with the measurement itself or the models being used to calculate the constant.

- If all of these measurements are found to be correct, however, new physics would be required to describe the universe.

Driving the news: In a study published today in the journal Science, a team of cosmologists, including Kelly, reports a constant of about 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec. - The value was determined by studying how the light arriving at Earth from a supernova is bent by the gravity of a galaxy cluster in its path, what's known as gravitational lensing. These two (or more) views of light from the same source traveling different paths can be used to calculate a value for the Hubble Constant.

- The finding is consistent with early universe measurements using the cosmic microwave background.

Yes, but: The approach comes with uncertainty. - The current study uses different models of the distribution of mass in clusters of galaxies to calculate the time it took for the light from the supernova to reach Earth. Those differences affect the value of the Hubble Constant.

- The authors of the new study looked at eight different models and selected the two that best matched their observations to arrive at their value. The uncertainty in the models means the value could be as high as 70.7 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

One notable aspect of the study is that it is an independent method that relies on measurements from an astronomical object not used in other studies that look at the CMB and different types of stars. What to watch: The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is providing new data about galaxies and stars that could inform the debate. The bottom line: "I am optimistic this legitimate discussion will wrap up one way or another," says Roger Blandford, an astrophysicist and professor at Stanford University. "It is a knowable thing ... the universe is cooperative in this sense." |     | | | | | | 2. Genome update |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | A first draft of a human "pangenome" that captures more of the genetic diversity in the human population was published yesterday. Why it matters: It's a major development that could help researchers find and better understand genetic variations linked to diseases and disorders. Genetic research and medical treatments have been hindered by a reliance on genomic data from white European populations. Background: The first draft of the human genome, published more than 20 years ago, was based largely on the genome of a single individual. It has since been used as the reference for understanding genetic variants in people. - But, "[n]o single genome can represent the genetic diversity of our species," researchers write in one of four papers published yesterday in Nature describing the work.

Driving the news: The new pangenome is a collection of sequences based on DNA from 47 people from around the world, including Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, Europe and the Americas. It was produced by the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium, a group of more than 120 scientists who are trying to sequence the genomes from 350 people by the middle of next year. - The new reference genome was made by aligning the different sequences and mapping where they diverged from one another.

- New "long-read sequencing" techniques that allow longer fragments of DNA to be analyzed compared to traditional sequencing methods and advanced computational tools helped enable the effort.

Yes, but: The pangenome hasn't captured the full genomic diversity of humans. People from the Middle East, Africa and Oceania are underrepresented, Evan Eichler, a professor of genome sciences at the University of Washington and member of the consortium, told The Washington Post. - And the clinical benefits of the pangenome aren't likely to be immediate, Tina Hesman Saey reports in Science News. Eichler said researchers first have to study how genetic variants affect diseases.

What to watch: Some researchers "are concerned that the project risks repeating ethically questionable practices from other large-scale genetic-diversity projects," Layal Liverpool writes in Nature. - Other projects have been criticized for not engaging enough with the underrepresented groups they are collecting samples from, and some experts are concerned people from those groups won't benefit from the research, she reports.

|     | | | | | | 3. NOAA: El Niño forming quickly and could be "significant" event |  Data: NOAA; Chart: Axios Visuals The odds are increasing that an El Niño event will form in the tropical Pacific Ocean this summer, hastening climate change and altering global weather patterns, according to a new National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) outlook, Axios' Andrew Freedman writes. The big picture: It could lead to the first year in which the global average surface temperatures bump up against the Paris Agreement's more stringent climate change target of 1.5°C (2.7°F) above preindustrial levels, Zeke Hausfather, climate research lead at payments company Stripe, tells Axios. - The waters of the equatorial tropical Pacific Ocean are warming quickly, and at least a moderate El Niño is expected to begin during the May-July period and continue into the Northern Hemisphere winter, NOAA stated today.

- The new outlook cites several trends for having increased confidence in El Niño's formation and intensity compared to just one month ago.

- These include: increasing sea surface temperatures; the presence of unusually warm waters beneath the surface, which are sloshing from the Western Pacific eastward; and shifting trade winds.

- In addition, computer model projections have grown steadily more bullish on both El Niño's development and intensity.

By the numbers: The odds of El Niño forming through July and lasting into the Northern Hemisphere winter are now at 82%, with above 90% odds later this summer, NOAA found. - This is up from just above 60% odds for the May-July period provided in April's forecast.

- The odds of at least a moderate El Niño at the end of the year are pegged at 80%, with about a 55% chance of a strong El Niño event.

Threat level: Global ocean surface temperatures have been off the charts in recent months, a trend linked to El Niño's formation. - El Niño events are naturally occurring, and the added ocean heat, some of which gets transferred into the atmosphere, serves to temporarily accelerate the rate of human-caused climate change.

- The last record warm year occurred in 2016, which also featured a strong El Niño.

- The planet has continued to warm since: The past eight years were the warmest eight years on record.

- This positions 2023 and 2024 well for coming close to or breaking new benchmarks.

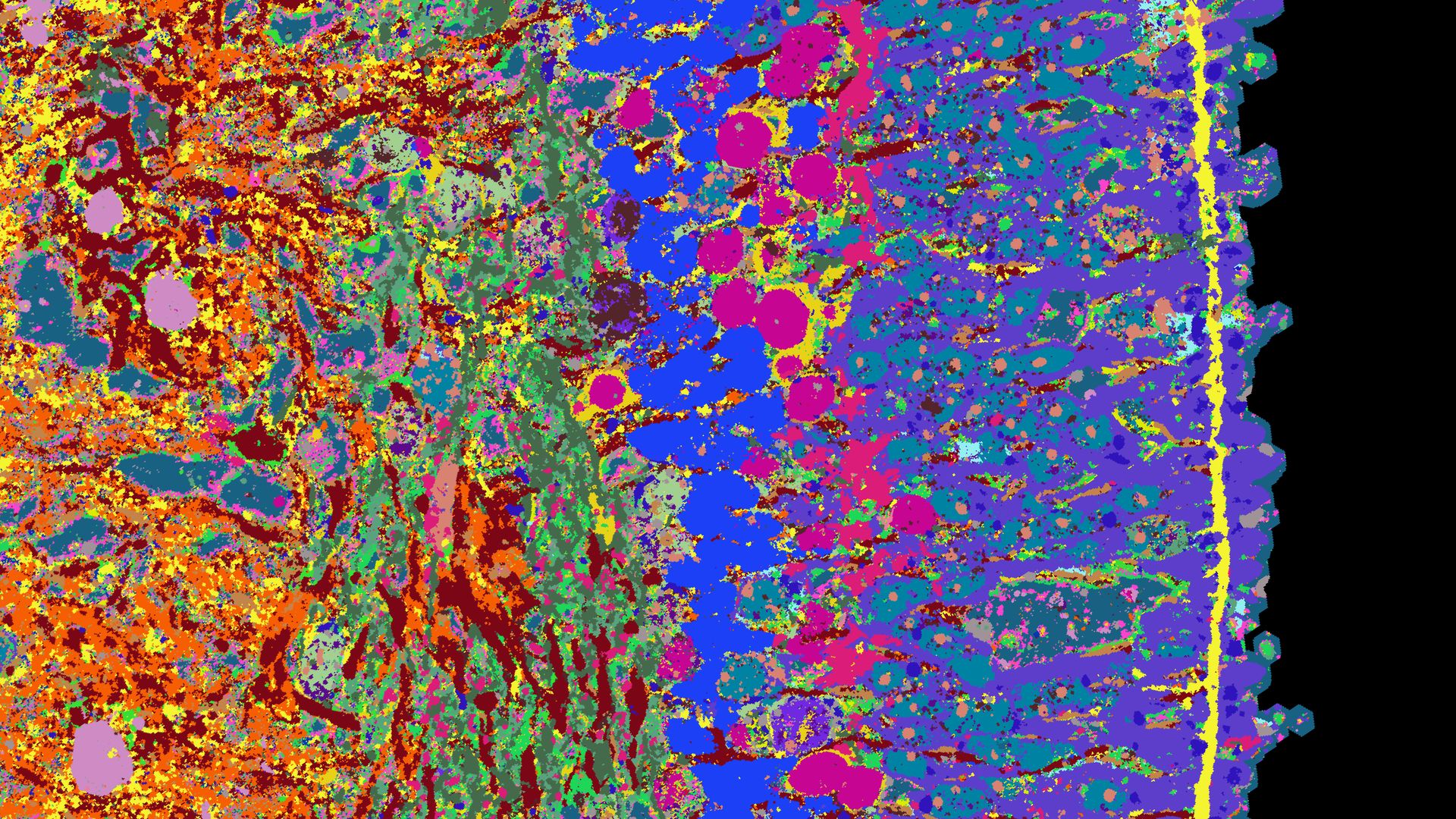

Read the entire story. |     | | | | | | A message from the University of Central Florida | | Butterflies inspire the world's first energy-saving paint | | |  | | | | University of Central Florida nano-scientist Debashis Chanda invented a safer, lighter, energy-efficient paint using colorless materials — instead of traditional pigment — to create color. Chanda drew his inspiration from butterflies reflecting vibrant colors. Learn about the innovation. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | Artificial intelligence is speeding up astronomy (Miriam Kramer — Axios) Mass walkout at global science journal over 'unethical' fees (Anna Fazackerley — The Guardian) A zoo association devoted to science, and plagued by scandal (Asher Elbein — Undark) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | Cross section of fluorescence-stained retinal organoid. Credit: Wahle et al. Nature Biotechnology 2023 | | | | A team of scientists used lab grown tissue to help create a high-resolution atlas of the cells involved in the development of the human retina. The big picture: Researchers are trying to map every cell in the human body in an effort to better understand how cells and tissues develop, and how they are affected by disease. Details: In a paper published this week in Nature Biotechnology, researchers in Switzerland report dyeing retinal tissue they grew from stem cells in the lab in order to create an atlas of cells in the retina. - They used a technique that involves dyeing the tissue, taking images, washing the dyes away, and dyeing the tissues again. The team used a robot to complete these steps 18 times over 18 days.

- The images were then combined into one and analyzed to see how many of the 53 different proteins were present and to study the role of rods, cones and other cells in the retina.

- The scientists studied organoids at different stages of development to try to understand the changes in cells, protein and genes as a retina forms during embryonic development, Gray Camp, a professor at the University of Basel and an author of the study said in a press release.

What to watch: The team plans to use drugs or genetic modifications to intervene with the development of the organoids — and study the effect, according to the press release. - "This will give us new insights into diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa, a hereditary condition that causes the retina's light-sensitive receptors to gradually degenerate and ultimately leads to blindness," Camp said.

|     | | | | | | A message from the University of Central Florida | | UCF researchers are harvesting sustainable energy | | |  | | | | New technology developed by University of Central Florida (UCF) engineers converts radio frequency signals into direct current electricity. Why it's important: Their discovery can help lessen the reliance on batteries and the growth of wireless systems amid expanding energy needs. Learn how. | | | | Thanks to Miriam for writing for this week's newsletter, to Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath for editing, to Natalie Peeples on the Axios Visuals team and to Jay Bennett for copy editing this edition. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? Your essential communications — to staff, clients and other stakeholders — can have the same style. Axios HQ, a powerful platform, will help you do it. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

To stop receiving this newsletter, unsubscribe or manage your email preferences. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments