| | | | | | | Presented By Brilliant | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · May 04, 2023 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. I was off for a few weeks grieving the unexpected death of my father. This week I look at what happens in the brain in the aftermath of a loss, something virtually all of us will experience. - This edition is 1,762 words, about a 7-minute read.

- Send your feedback and ideas to me at alison@axios.com.

- Sign up here to receive this newsletter.

| | | | | | 1 big thing: How the brain grieves |  | | | Illustration: Maura Losch/Axios | | | | When we lose a connection to someone, the brain changes as we grieve. Why it matters: Grief is an intense emotional experience. Some researchers say a better understanding of the biological effects of loss on the brain could be used to help ease the pain and yearning experienced in grieving. - "We don't want to get rid of grieving experiences but maybe people don't need to have profound detrimental effects on their health," says Zoe Donaldson, a professor of neuroscience at the University of Colorado Boulder.

- Grief often extends beyond our emotions to our thoughts, behaviors and body. It may increase the risk of a heart attack just after a loved one dies and has been linked to an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, cancer and other chronic diseases. Parents who lose a child before reaching mid-life may have an increased risk of developing dementia later in life.

- Most people adapt to their loss but for some — an estimated 5-10% of people who have lost someone — grief can be prolonged.

How it works: The bonds we form with one another take biological forms in the brain — changes in hormones, the expression of genes and more. - These neural maps inked from our experiences with someone frame the brain's predictions of our world that guide us through life: A partner who usually gets home first, a parent who calls on a birthday or a friend who joins you for coffee every week.

- Studies have found the brain's reward systems are activated by these relationships, motivating us to maintain these bonds and reunite with loved ones regularly.

"The trouble is that with the death of the loved one, that solution doesn't work anymore," says Mary-Frances O'Connor, a professor of clinical psychology and psychiatry at the University of Arizona, and the author of "The Grieving Brain: The Surprising Science of How We Learn from Love and Loss". - Instead, there are conflicting streams of information: There is a memory of a funeral or a phone call with news that someone died, and a neurobiological attachment that says they are still here, she says.

- As a result, people can experience what Donaldson calls "unrequited yearning" — a frustrating state in which we seek someone but the brain isn't rewarded with their presence.

- "Grieving takes a long time to resolve these two streams of information and for the brain to be able to predict their absence instead of predicting their presence," says O'Connor, who conducted early studies on the neuroimaging of grieving 20 years ago. She describes it as a process akin to learning.

Details: Some researchers study the bonding behaviors of monogamous prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) as proxies for human attachment. The small rodents are a little larger than a mouse and form lifelong bonds with mates in the lab or in the wild. - Studies have found that as prairie voles first bond, a set of genes associated with learning and memory turns on. As they settle into their partnership, a different pattern of genes in the brain's reward systems is expressed.

- When a prairie vole loses a partner, it appears stressed for some time but eventually is able to form new bonds. In the time in between, "many of the changes of the brain in forming a bond erode though it is not an entire reset," Donaldson says.

|     | | | | | | 2. Part II: Studying connection and loss | | A pair of recent studies by Donaldson and her colleagues provides details about how memories might be uncoupled from yearning during grieving. - In one new study, pairs of voles were housed together for two weeks. They were then separated from one another after 48 hours or four weeks, and the team looked at which genes were turned on and off in the nucleus accumbens, a site in the brain that plays a role in its reward system and social bonding.

- The researchers found a set of genes was expressed in male voles while they were with their partners and for at least two days after the voles were separated.

- Over four weeks of separation, that pattern of gene expression eroded. But, surprisingly, the males remembered — and preferred — their partner.

- Those genes could be involved in recovering from the loss of a partner, Alison Bell, who studies animal behavior and wasn't involved in the study, wrote in an accompanying article. But the researchers acknowledge the pattern of expression for these genes could be different from those in other brain regions involved in bonding that could help to maintain attachments.

In a second study, not yet peer-reviewed, Donaldson and her colleagues looked at the brain basis for yearning in prairie voles. - Voles were trained to press levers that opened doors — one to their partner and another to a vole they didn't know.

- The voles pressed both levers but, using a tool to measure the release of dopamine in the brain at the sub-second level, the scientists found more dopamine was being released in the nucleus accumbens when they interacted with their partner. It happened when they were hitting the lever and anticipating reuniting with them and when the door opened and they were actually together.

- When they separated the voles for four weeks, less dopamine was released when they were reunited. They could remember their partner and would still go to them but the "reward is blunted to a point where there is no difference" and they could form a new bond.

- The team suggests the erosion of dopamine release during separation is "a potential mechanism for overcoming loss."

Keep in mind: Bonding in prairie voles and humans has some similarities but human love is "enriched by our complex understanding of ourselves and our most significant others," Donaldson and her colleagues recently wrote. What to watch: There is an ongoing debate about when "normal" grief becomes pathological. Understanding the neurobiology of changes in the brain after a loss would help to inform that question as well as those about grief and its relationship to depression and loneliness. - Grief and depression overlap and intersect but evidence suggests they are distinct.

- Grieving involves processing someone's death — we go over what happened in our minds. But rumination is a feature of depression and can have negative consequences. The question is, "How much of it is good, and when does it become problematic?" O'Connor says.

The bottom line: "As difficult as an experience grief is, from the perspective of the brain's mechanisms, grief is a normal protective process," says Lisa Shulman, a neurologist at the University of Maryland and author of "Before and After: A Neurologist's Perspective on Loss, Grief and Our Brain." - "The more we can understand that, the more we can have some comfort with some of the strange periods we can have during periods of loss."

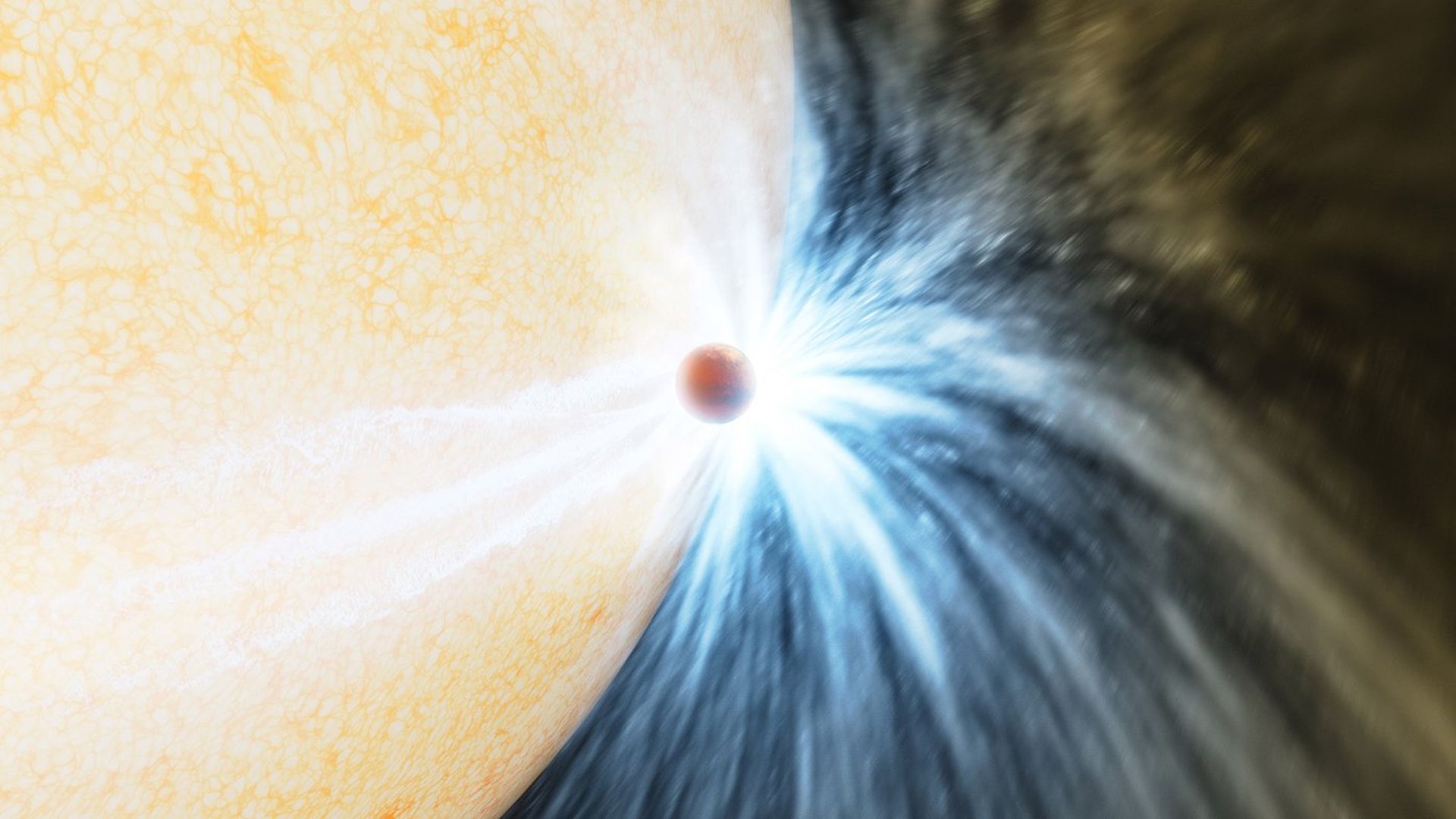

|     | | | | | | 3. Distant star caught swallowing its own planet |  | | | Artist's illustration of a planet being absorbed by its star. Image: K. Miller/R. Hurt (Caltech/IPAC) | | | | A Sun-like star 12,000 light-years from Earth has been spotted eating one of its planets, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes. Why it matters: The first-of-its-kind discovery is a glimpse into the future of our solar system. In about 5 billion years, our Sun will expand, consuming Mercury, Venus and even Earth. - "The confirmation that Sun-like stars engulf inner planets provides us with a missing link in our understanding of the fates of solar systems, including our own," Kishalay De, a researcher at MIT and lead author of a new study in Nature detailing the discovery, said in a statement.

What they found: When the team of scientists started observing the star with the Zwicky Transient Facility, they saw it brighten in optical light — the spectrum of light the human eye can see. - But follow-up observations with other instruments showed the star was also brightening in infrared light, which could point to the creation of dust in the system.

- The team of scientists then figured out that as the planet fell into its star's expanding atmosphere it displaced hot gas from the star that then cooled and created dust. Fragments of the planet also blew outward from the star, producing more dust.

- "The planet plunged into the core of the star and got swallowed whole. As it was doing this, energy was transferred to the star," De added. "The star blew off its outer layers to get rid of the energy. It expanded and brightened."

The bottom line: Learning more about these distant star systems is bringing us closer to truly understanding the eventual fate of the Earth and our Sun. |     | | | | | | A message from Brilliant | | Sharpen your math, CS and data skills in a few minutes a day | | |  | | | | For professionals and lifelong learners alike, Brilliant is one of the best ways to learn. The deets: Bite-sized interactive lessons make it easy to level up in everything from math and data science to AI and beyond. Join 10+ million people building skills every day. Start with a free 30-day trial. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | The foul chartreuse sea (Saima Sidik — Hakai) Inside the fight to save a beleaguered butterfly (Ben Goldfarb — High Country News) The mystery behind the unique chemistry of Earth's continents (Laura Baisas — Popular Science) |     | | | | | | 5. Someone wondrous |  | | | My dad. Photo: Paul Reuter | | | | My dad, David Snyder, was an engineer to his core. He could fix anything, bring seemingly unrealistic ideas into being, and simply loved to solve problems. The big picture: My dad passed away on March 29. In the days and weeks since, I've thought a lot about his part in a generation of scientists and engineers who built the world we live in today, where we can communicate instantly and learn endlessly. - For more than 20 years, he was an engineer at Bell Labs, and he spent decades more with other companies and startups. He worked on the fiber optic link that was the precursor to what is now known as FireWire. The chips he designed in the 1990s were the workhorse for most of the transmitters sold by AT&T and Lucent Technologies. And he helped to develop silicon photonics technology for fiber optics that is ubiquitous in the telecommunications industry.

- My dad was also a master tinkerer and creator: He built a Tesla coil (and a machine to build the Tesla coil), converted a schoolhouse into our family home, engineered epic Slip 'N Slide modifications, designed and constructed a weather station before they could be ordered in one piece on the internet, and created countless other tools, toys and objects at the intersection of art and engineering.

Those were some of his gifts to the world. One of his greatest gifts to me, though, was the lens of science for seeing the world. - I greatly admire my dad's curiosity, creativity, conscience and optimism — human traits of the scientific endeavor at its very best.

- Science — by doing it, talking and writing about it, and scrutinizing it — has given me a path to walk through this world. It's not the only one, and it has its flaws and blind spots, but it offers a worldview hued with beauty and wonder and it can be a force to move forward.

- My dad opened that path for me, and I'm forever thankful to him.

|     | | | | | | A message from Brilliant | | AI won't take your job, but someone using AI will | | |  | | | | Future-proof your skill set with Brilliant and learn the concepts behind tech like AI, neural networks and more. Here's how: Brilliant's bite-sized interactive lessons let busy people grow their skills in minutes a day. Join 10M+ people learning on Brilliant — try it for free, then get 20% off. | | | | Big thanks to editor Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath, to Miriam Kramer for writing for this week's edition and to copy editor Carolyn DiPaolo. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? Your essential communications — to staff, clients and other stakeholders — can have the same style. Axios HQ, a powerful platform, will help you do it. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

To stop receiving this newsletter, unsubscribe or manage your email preferences. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments