| | | | | | | Presented By the University of Central Florida | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · May 25, 2023 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This edition is 1,652 words, about a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Worries mount about misinformation in science |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | Misinformation and disinformation are diminishing public trust in science and becoming an existential threat to the planet, researchers warned this week. The big picture: False information about vaccines and climate change — runs rampant on social media, where Americans are increasingly getting their news and information. - At the same time, a gap in trust of scientists is widening along political lines: In a Pew Research survey last September, 24% of Republicans said they think scientific experts are typically better than others at making good policy decisions about scientific issues, compared to 55% of Democrats.

- The causes and the effects of these intersecting trends are the focus of a three-day meeting this week in Washington, D.C., organized by the Nobel Foundation and the National Academy of Sciences.

Details: Speakers described how the attention economy's business model intersects with the very human desire to belong — fueling an information environment riddled with misinformation and disinformation. - "The real problem isn't people. It's the reward structure on social platforms," said Gizem Ceylan, a behavioral scientist at Yale University.

- In a study published this year, Ceylan found the rewards — attracting attention and recognition in the form of likes and comments — of sharing online create habits that drive people's behavior more than their motivations do. For example, the top 15% of habitual news sharers were involved in 30% to 40% of the false news shared in the study.

- Earlier research zeroed in on people's desire to be a source of novel information — which was more likely to be false — as helping to drive the spread of misinformation and disinformation on Twitter.

- Ceylan and her collaborators argue "social media sites could be restructured to build habits to share accurate information."

Providing accurate information isn't enough, several speakers emphasized. - "Our information problems today are not just technological ones. We aren't going to be able to fact check or innovate or police away racism and information harmful to our digital spaces," said Rachel Kuo, a professor of media studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

- "Information has always been bound up in social, economic and political systems and structures," she added.

And finding reliable sources of information is difficult because of changes in society in recent decades, said Hahrie Han, a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University. - We now have more social interactions than social relationships and the relationships we do have are more likely to be transactional, she said. And if they are actual social relationships, they are more likely to be with people who are like us because of the disintegration of civic infrastructure, she added. That fuels "echo chambers where disinformation can bounce around."

- Han conducted research with one of the largest megachurches in the U.S. and says the church motto of "belonging comes before belief" should be leveraged to create relationships of belonging with people across the "social spaces we inhabit."

- "When we think about combating misinformation, we have to address not only the narratives and the ideas, but also the social infrastructure that underlies how you're interacting with information," said Han.

Of note: Several speakers held up peer review as science's own process of vetting information. - But the scientific enterprise — the incentives for scientists to publish and for journals to attract readers, jargon and other features of scientific publishing — can also contribute to the spread of misinformation.

What to watch: Researchers presented findings from the first report of the International Panel on the Information Environment (IPIE), a group formed to assess tools to combat misinformation and disinformation, and inspired by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). - Analyzing nearly 600 peer-reviewed studies, they found scientific evidence supports labeling content (tagging about fact-checking, funding and other information that provides context) and publishing corrections to help people assess information on social media. There was less scientific consensus about moderating content.

- They also made some recommendations for scholars studying misinformation, including standardizing definitions of misleading information and analyzing non-English language sources.

The bottom line: Misinformation is "so far-reaching that it is rapidly becoming an existential threat to the planet," said Sheldon Himelfarb, executive director of IPIE. |     | | | | | | 2. Nearly 2 billion at risk from "unprecedented" climate conditions |  | | | Illustration: Brendan Lynch/Axios | | | | Absent new, more ambitious climate policies, the world is headed for a magnitude of climate change that would put about 2 billion people at risk of extreme heat by the end of the century, a new study finds, Axios' Andrew Freedman writes. The big picture: Extreme heat this week illustrates the challenges some countries are already facing, with temperatures in Delhi, India, reaching 46.5°C (115.7°F) on Monday. Why it matters: Limiting global warming to the Paris Agreement's target of 1.5°C (2.7°F) above preindustrial levels would yield a five-fold reduction in the population exposed to unprecedented heat by the end of this century. - The nearly 1.2°C (2.16°F) increase in global average surface temperatures to date has already knocked more than 600 million people out of the "human climate niche" in which society has historically thrived.

- The researchers of the new study, published Monday in Nature Sustainability, define that niche by looking at how human population density varies with temperature and precipitation.

The intrigue: They find two peaks in population density, one associated with a mean annual temperature of about 13°C (55.4°F), and the other tied to more tropical climates, at 27°C (80.6°F). - Outside of these temperatures, conditions tend to be either too wet or dry, or too hot or cold, for high concentrations of people to thrive, the study states.

Between the lines: The researchers sought to shed light on the current and projected human toll of climate change. - Unprecedented heat exposure is defined as having a mean annual air temperature of 84.2°F (29°C), which the scientists found correlated with more frequent spikes to greater than 40°C (104°F), and potentially lethal wet bulb temperatures of greater than 28°C (82.4°F).

- Wet bulb temperatures incorporate humidity; once they climb to about 35°C (95°F), they can cause potentially fatal heat-related illness by impeding the human body's ability to cool itself through sweat.

Of note: The study found that if countries only meet emissions reductions based on current policies, and warming were to reach 2.7°C by 2100 (4.8°F), the top five countries most vulnerable to unprecedented heat (based on the number of people exposed) would be India, Nigeria, Indonesia, the Philippines and Pakistan. Read the entire story. |     | | | | | | 3. Researchers define long COVID symptoms |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | Researchers have identified a dozen symptoms that most commonly characterize long COVID, based on an analysis of nearly 10,000 participants in a National Institutes of Health effort to study the long-term health effects of the virus, Axios' Arielle Dreher writes. Why it matters: Though more than 658 million people worldwide have been infected with the virus, researchers said most studies have focused on defining long COVID based on the frequency of individual symptoms — and have generated widely divergent estimates of their prevalence. - As many as 23 million Americans continue to experience COVID symptoms six months or more after initial infection, and understanding the most common symptoms can better help diagnose and treat cases.

What they found: Researchers found 37 symptoms as present more often in infected participants at six months or longer after infection, then winnowed that list to the dozen most distinct symptoms. - Those include malaise after exertion, fatigue, brain fog, dizziness, gastrointestinal symptoms, heart palpitations, changes in sexual desire, loss of smell or taste, thirst, chronic cough, chest pain and abnormal movements.

- Some symptoms are more likely to occur together, researchers found and identified subgroups of patients who experienced similar symptoms.

- The broad range of symptoms could be related to factors such as viral reservoirs that remain in the body and perpetuate the infection, the researchers concluded.

- The study confirmed findings that long COVID can affect multiple organ systems in the body.

- Patients were more likely to report having long COVID and have more severe symptoms if they were infected before the Omicron variant began circulating, the researchers wrote in JAMA.

What's next: The study is the first published data from NIH's RECOVER initiative, a $1 billion effort to define and study long COVID. - It's been criticized for not signing up patients to test potential treatments, STAT reported.

- Future RECOVER-based studies will look at lab tests and imaging associated with patients' reported symptoms.

|     | | | | | | A message from the University of Central Florida | | UCF trains next-generation nurses with simulation technology | | |  | | | | The University of Central Florida's (UCF) nursing simulation center replicates health care settings using augmented, virtual and mixed reality to foster learning. - The center is one of few worldwide and the only one in Florida to earn the Healthcare Simulation Standards Endorsement.

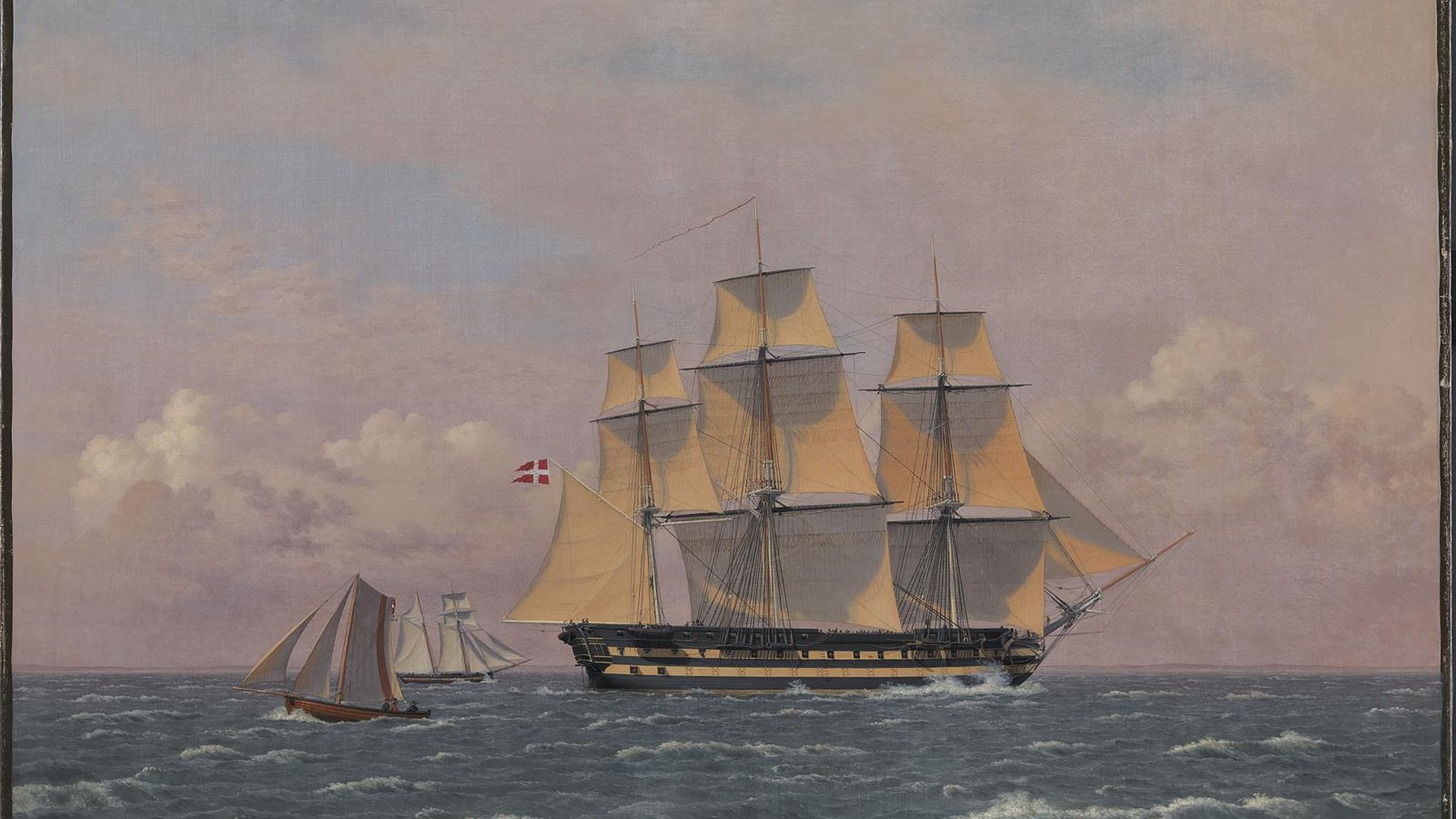

Learn more. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time |  | | | Patient and scientist walking with digital bridge at Lausanne University Hospital, EPFL. Photo: Jimmy Ravier | | | | A brain implant helped a man with paralysis walk more naturally (Simon Makin — Science News) How the U.S. debt-ceiling crisis could cost science for years to come (Jeff Tollefson — Nature) The neurons that make us feel hangry (Amber Dance — Knowable) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | C.W. Eckersberg, "The 84-Gun Danish Warship 'Dronning Marie' in the Sound" (KMS255). Credit: Statens Museum for Kunst (Copenhagen, Denmark) | | | | Danish paintings from the first half of the 19th century contain the byproducts of beer brewing, researchers reported this week. Why it matters: The new information about the ingredients artists used to prime their canvases will assist with preserving the paintings from the Danish Golden Age, a period of immense creative production. - The manuals of local artists suggested a recipe made from the byproducts of beer was used to prepare canvases in the workshops of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. But there wasn't any empirical evidence.

What they found: Chemists and conservationists in Denmark studied 10 paintings by Danish artists Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg and his protégé Christen Schiellerup Købke. - Using mass spectroscopy, the team identified wheat, barley and other cereal proteins as well as baker's yeast proteins in seven of the paintings.

- The proteins act as a binder for the paint and their most likely source is beer brewing, according to the study in Science Advances.

The big picture: The scientific analysis of artwork not only aids art conservation but allows artwork to be used as "'historical molecular records' of the culture and the society from which they originate," the authors write. |     | | | | | | A message from the University of Central Florida | | New lightning-fast battery could help prevent electric vehicle fires | | |  | | | | University of Central Florida researcher Yang Yang developed a battery that replaces the highly flammable organic solvents found in electric vehicle batteries with salt water. This technology creates a safer, faster-charging alternative that won't short-circuit during floods. Learn more. | | | | Thanks to editor Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath, Aïda Amer on the Axios Visuals team, and Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing this edition. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? Your essential communications — to staff, clients and other stakeholders — can have the same style. Axios HQ, a powerful platform, will help you do it. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

To stop receiving this newsletter, unsubscribe or manage your email preferences. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments