| | | | | | | Presented By Brilliant | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · May 18, 2023 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This edition is 1,521 words, about a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: Plant science's biggest problems |  | | | Illustration: Natalie Peeples/Axios | | | | Plant scientists are increasingly concerned about how plants will fare as climates change across the planet — and what role plants themselves can take in addressing one of the world's most pressing problems. Driving the news: A recent survey takes the pulse of the plant science community — a group of researchers whose subjects are often overlooked but critically support life on Earth. - An international panel of 15 researchers from five continents analyzed more than 600 questions collected from plant scientists, horticulturalists, gardeners, other experts and "botanically curious non-experts."

- They identified 100 pressing questions facing plant science, ranging from how plant scientists can collaborate with city designers and how plants can be grown in space to fundamental questions about plant pathogens and the genomes and evolution of plants.

- More than 20% of the questions focused on climate change: how it will affect plant diseases and where plants can grow, as well as whether farming seaweed and other crops under the sea could reduce the impact of climate change, among other topics.

Flashback: When a similar survey was done in 2011 the questions focused more on what could be learned from plants. - "This time around the questions were more about, 'what do we do to save them?'" says Emily May Armstrong, an interdisciplinary plant researcher and co-author of the study that appeared in New Phytologist.

- There were also questions focused on determining which plants can best help the capture of carbon in soil, how plants can mitigate flooding, and how microbiomes can be leveraged to develop plants that can help to mitigate the effects of climate change.

What's happening: Plant scientists are studying a range of climate-related topics. These include: - Seagrass as a way to capture and store carbon. A key question is what traits give these plants the ability to efficiently remove carbon.

- Sequestering carbon in other plants — trees and crops.

- Increasing the efficiency of photosynthesis and developing climate-resilient crops

- Plants — such as switchgrass and black cottonwood — as a source of biofuel

What they're saying: Climate change is "an enormous obstacle that will require a multidisciplinary approach. It affects molecular, physiological, ecological and all levels of plant growth and the plant life cycle," says Marie Klein, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Davis, who organized the "Plants in the Climate Crisis" symposium held last week at the university. What to watch: The survey organizers say the questions highlighted the importance of including scientists worldwide, insights from non-experts, and the need for more funding. - "This time they heard the voice of the Global South," says Shyam Phartyal, a seed ecologist at Nalanda University in Rajgir, India, and co-author of the paper.

- Plant sciences continue to struggle with biases: A recent study of more than 300,000 scientific articles published in the field over the past 20 years found "authors in Northern America are cited nearly twice as many times as authors based in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, despite publishing in journals with similar impact factors," Rose Marks of Michigan State University and her colleagues wrote earlier this year in the journal PNAS.

- They also found gender imbalances that tip to male authors and that most studies "focus on economically important crop and model species, and a wealth of biodiversity is underrepresented in the literature."

|     | | | | | | 2. Mangroves get connected on the Indian coast |  | | | Connected Mangrove project site in Porbandar on the Gujarat coastline. Photo: Ericsson | | | | Mangroves are being planted along the Saurashtra coast of India and outfitted with sensors to track their health and growth. Why it matters: Mangroves act as barriers that protect land, prevent soil erosion and the impacts of other natural hazards being fueled by climate change, and absorb carbon dioxide. They are also home to many species, including fish and shellfish that are a source of food and jobs for nearby communities. Details: The Connected Mangroves project, which telecommunications giant Ericsson launched in India last month in partnership with the Aga Khan Agency for Habitat (AKAH) India, planted 100,000 mangrove saplings and 20,000 fruit-bearing plants in 10 villages in Gujarat. - Sensors and other devices will measure temperature, humidity, soil moisture and other indicators of the health of the mangroves. The data is shared with local authorities, growers, NGOs and others that then make decisions to aid in reforestation and land use.

Background: The project first started in 2015 in Malaysia where the company said the percentage of mangroves that matured doubled from 40% to 80% over a year. Seedlings often don't grow due to a lack of water, fire, pollution and other factors. - Two years later, Ericsson took the project to the Philippines.

The big picture: The project is part of a broader push to use sensors, drones and 5G to monitor forests' vital signs. - Vodafone is putting gas sensors on trees in Sardinia and elsewhere in Spain to detect forest fires. The company and others are also using acoustic sensors in forests in Romania and elsewhere to try to stop illegal deforestation.

- Researchers are trying to use AI to count tree-killing pine weevils spotted by cameras in a forest in Scotland — information that could help foresters decide whether and when to plant pine or spruce trees that underpin the timber industry.

What to watch: Some researchers have raised concerns that digitalizing forests to produce data for conservation efforts could be costly for a field with limited funding if technology has to be upgraded often. - They are also concerned traditional stakeholders won't have equal access to and influence over technologies that could change conservation as companies that develop and deploy them, sociologist Danilo Urzedo of the University of Cambridge and his colleagues wrote last year.

|     | | | | | | 3. Future of food production hinges on water |  Water resources in the Continental U.S. are threatened by climate change, groundwater overdraft and longstanding water quality issues. One example is the Ogallala Aquifer, which is found in parts of eight states. Data: USGS; Map: Axios Visuals A team of more than 40 USDA scientists has listed the most significant looming challenges facing water resources and agricultural production nationwide, Axios' Ayurella Horn-Muller writes. Why it matters: Their newly released plan unlocks a 30-year roadmap for mitigating some of the leading issues imperiling water sustainability before they become full-blown crises. What they found: According to a summary of their findings published last week in the Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, the main challenges through the year 2050 are supply shortages, flood risk and water quality. - Led by scientists at the Agricultural Research Service, the article highlights how continued development of irrigated agriculture is "diminishing critical aquifers" as limited water resources will confront increasing demand under rising temperatures.

Threat level: The water levels in the Ogallala Aquifer — one of the world's largest fresh groundwater sources — are already plummeting, per KMUW. - Much of the most agriculturally productive areas of the aquifer are facing the risk of depletion by 2100 due to drought, farm irrigation and decades-long over-allocation.

- "Water in the Ogallala Aquifer has been severely depleted, particularly in the southern end of the aquifer. Continuing typical water withdrawals puts the aquifer, and the agricultural economy that relies upon it, at risk," says Emile Elias, director at the USDA Southwest Climate Hub and lead author of the article.

Meanwhile: Wildfires and shifting climate patterns imperil water sources on forested lands, as reservoirs "face dwindling inflows and are filling with sediment, increasing flood risk and reducing their capacity to respond to drought," per the paper. Zoom out: Climate change exacerbates water scarcity worldwide, which leads to agricultural declines that can trigger increasing food insecurity, according to a 2023 UN report. What they're saying: "We don't want to lose a drop of water in the future. Every drop matters," says Teferi Tsegaye, co-author of the article and national program leader for water resources at the Agricultural Research Service. - "The future of food production is dependent on freshwater."

Go deeper |     | | | | | | A message from Brilliant | | AI won't take your job, but someone using AI will | | |  | | | | Future-proof your skill set with Brilliant and learn the concepts behind tech like AI, neural networks and more. Here's how: Brilliant's bite-sized interactive lessons let busy people grow their skills in minutes a day. Join 10M+ people learning on Brilliant — try it for free, then get 20% off. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | Genetics study offers clues about why COVID is life-threatening for some people (Heidi Ledford — Nature) More than half of the world's largest lakes are drying up (Nikk Ogasa — Science News) Ancient Mesopotamian texts show when and why humans first kissed (Jocelyn Solis-Moreira — Popular Science) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | Siler collingwoodi. Photo: Yuchang Chen | | | | A colorful jumping spider protects itself from predators by imperfectly mimicking the moves of different ant species, researchers reported this week. The big picture: Other spiders act like ants but Siler collingwoodi doesn't mimic ants in its habitat perfectly — and that could help them survive, Sam Jones reports for the NYT. Details: Researchers at Peking University in China compared the movements of S. collingwoodi, a jumping spider that doesn't mimic ants and five ant species. Some predators avoid ants because they can be venomous or have spines that protect them. - They found the movements of S. collingwoodi — how they lifted their legs when they walked or moved their abdomens — were most similar to three of the smaller ant species.

- When the spiders' predators (a praying mantis and another jumping spider) were introduced, the mantid ate both the mimicking and non-mimicking spiders whereas the predator spider didn't attack S. collingwoodi, the researchers report in the journal iScience.

- They also found the ant-mimicking spider's brilliant color provided camouflage from predators when it was on a red-flowering jasmine.

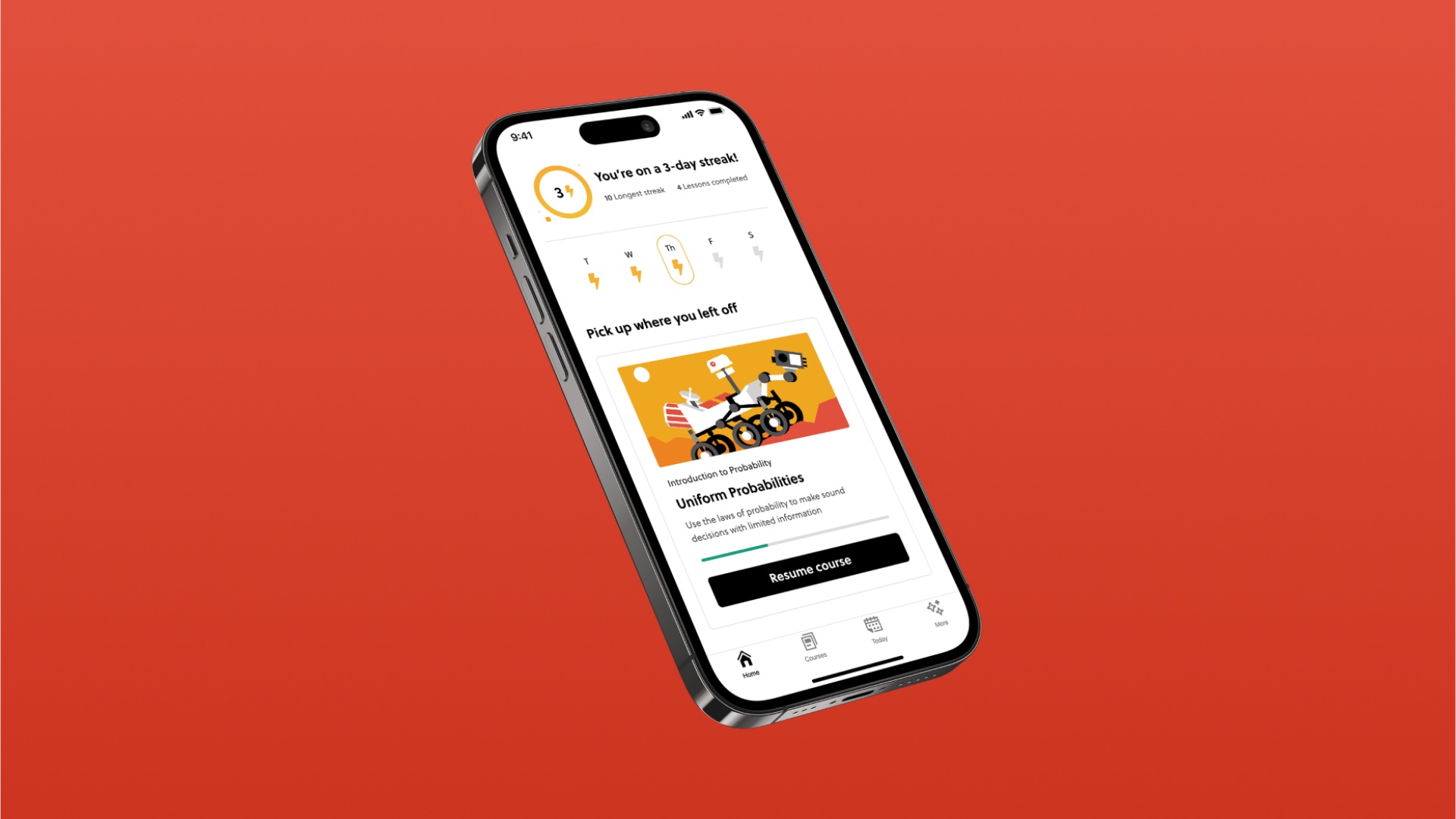

The intrigue: "Being a general mimic rather than perfectly mimicking one ant species could benefit the spiders by allowing them to expand their range if the ant models occupy different habitats," Hua Zeng, an ecologist at Peking University and author of the study said in a statement. |     | | | | | | A message from Brilliant | | Sharpen your math, CS and data skills in a few minutes a day | | |  | | | | For professionals and lifelong learners alike, Brilliant is one of the best ways to learn. The deets: Bite-sized interactive lessons make it easy to level up in everything from math and data science to AI and beyond. Join 10+ million people building skills every day. Start with a free 30-day trial. | | | | Thanks to editor Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath, Natalie Peeples on the Axios Visuals team, and Carolyn DiPaolo for copy editing this edition. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? Your essential communications — to staff, clients and other stakeholders — can have the same style. Axios HQ, a powerful platform, will help you do it. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

To stop receiving this newsletter, unsubscribe or manage your email preferences. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments