| | | | | | | Presented By the University of Central Florida | | | | Axios Space | | By Miriam Kramer · May 16, 2023 | | Thanks for reading Axios Space. At 1,397 words, this newsletter is a 5-minute read. - Please send your tips, questions and links in the supply chain to miriam.kramer@axios.com, or if you received this as an email, just hit reply.

| | | | | | 1 big thing: Growing the supply chain to space |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | Government and commercial interest and investment are spurring a new industrial base for the space industry. Why it matters: The transformation will set up the space economy for the coming decades, playing a major role in just how much the industry can grow. - Today's space supply chain includes satellite manufacturers, instrument specialists and rocket companies, among others. The industry has gone from largely bespoke to far more plug-and-play than it used to be.

- "Companies that started out with a vision of services are now also part of the supply chain in a new way," BryceTech CEO Carissa Christensen tells me.

What's happening: Companies are changing the way they operate on Earth in order to meet government and private demand. - Government entities like NASA and the Department of Defense are no longer looking to just buy satellites and spacecraft made especially for them for every mission.

- Instead, they and private customers are increasingly willing to buy more generic products — like standardized satellite bodies — that are less expensive and can be used with instruments either developed in-house or provided by others.

- Companies themselves are also partnering with others to build out their own constellations of satellites that can be composed of tens, hundreds or thousands of spacecraft.

For example: Maxar announced in April that it is rebranding its portfolio, offering customers a family of different-sized satellite bodies to choose from for any orbit or mission. - Instruments best suited to any given mission will be able to be added to those satellite bodies and get sent to space.

- "We are really now looking at the industrialization of space, not a bespoke mission here, bespoke mission there," Daniel Jablonsky, president and CEO of Maxar, told me in April at the National Space Symposium.

- "GEO satellites were manufactured one at a time, and now we've got companies with factories that are producing dozens or hundreds or thousands of small [satellites], that's really different," Christensen said.

The big picture: The space industrial base used to be largely composed of big, government aerospace contractors like Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon and others providing hardware that was highly specific to each of their customers. - As relatively new companies enter the supply chain, they're "creating competitive pressure on the companies that have been there a long time, and they're operating differently," Christensen said.

- "I'm looking to partner" with other companies, Robert Lightfoot, the executive vice president of Lockheed Martin Space, told me at the symposium. "The goal is not to buy them. The goal is to help grow the industrial base, not shrink it. ... So that's a different model for us."

|     | | | | | | 2. Tension over the Hubble Constant |  | | | Illustration: Natalie Peeples/Axios | | | | New observations and sharper tools are fueling the debate over a long-sought measurement of how fast the universe is expanding, I write with my colleague Alison Snyder. Why it matters: A resolution would determine whether scientists' model of the universe is broken or if it's missing something — and would answer key questions about the age, size and history of the universe. Where it stands: For more than 100 years, scientists have tried to figure out just how fast the universe is expanding, a key measurement known as the Hubble Constant. - Cosmologists who study changes in the cosmic microwave background — an imprint of radiation left on the universe just after the Big Bang — are circling around a measurement of 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

- Others who have used the brightness of certain stars to gauge the distance to them are finding the constant's value to be about 74 kilometers per second per megaparsec. Theirs is a measurement of events and features of a more mature universe, many of which were captured by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Driving the news: In a study published Thursday in the journal Science, a team of cosmologists reports a constant of about 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec. - The value was determined by studying how the light arriving at Earth from a supernova is bent by the gravity of a galaxy cluster in its path, what's known as gravitational lensing. These two (or more) views of light from the same source traveling different paths can be used to calculate a value for the Hubble Constant.

- The finding is consistent with early universe measurements using the cosmic microwave background.

Yes, but: The approach comes with uncertainty. - The current study uses different models of the distribution of mass in clusters of galaxies to calculate the time it took for the light from the supernova to reach Earth. Those differences affect the value of the Hubble Constant.

What to watch: The James Webb Space Telescope is providing new data about galaxies and stars that could inform the debate. - Large ground-based telescopes in the works — the Giant Magellan Telescope and the Thirty Meter Telescope — will provide even more precise and sensitive data for measuring the universe's expansion.

Subscribe to Alison's weekly Axios Science newsletter. Read more and share this story. |     | | | | | | 3. Solar storm predictions |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | An AI tool developed by NASA could warn people on Earth before a major solar storm impacts the planet. Why it matters: Solar storms can knock out radio communications, harm satellites and people in space, and — in extreme cases — disable power grids on Earth. - A solar storm in 1859 known as the Carrington Event lit telegraph lines on fire, but experts warn a serious solar storm like that today could do massive harm to our electronics-dependent world.

Driving the news: The computer model — created by Frontier Development Lab, which is a partnership of organizations including NASA, the Department of Energy and U.S. Geological Survey — can predict solar storms 30 minutes before they reach Earth, according to the space agency. - Other computer models have been used to forecast geomagnetic storms for specific parts of the planet, but this computer model is able to quickly predict these storms globally.

- "With this AI, it is now possible to make rapid and accurate global predictions and inform decisions in the event of a solar storm, thereby minimizing — or even preventing — devastation to modern society," Vishal Upendran of the Inter-University Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics, the lead author of a study about the new model published in Space Weather, said in a NASA press release.

- Scientists checked the accuracy of the model by testing it against two historic solar storms — one in 2011 and one in 2015. They found the AI model was accurate in its forecasting of the impacts of those storms globally.

How it works: The Sun emits a constant stream of charged plasma particles known as solar wind that impacts and warps planets' magnetic fields. - Sometimes sunspots unleash huge bursts of solar plasma — called coronal mass ejections — that can supercharge space weather, creating brilliant auroras like those seen in recent weeks.

- But those CMEs can also be dangerous, and as the Sun nears the peak of its 11-year solar cycle in the coming years, the risk of a major geomagnetic storm also increases.

The bottom line: Having the ability to forecast solar storms quickly and with an eye toward global impacts could potentially reduce the chances of space weather wreaking havoc on our modern way of life. |     | | | | | | A message from the University of Central Florida | | UCF is America's Space University | | |  | | | | With NASA funding, University of Central Florida researchers are advancing space science to explore the Moon — and beyond. Faculty researchers: - Produce experimental Lunar simulant for global partners.

- Expand the potential of spacecraft safety.

- Support NASA's Artemis missions.

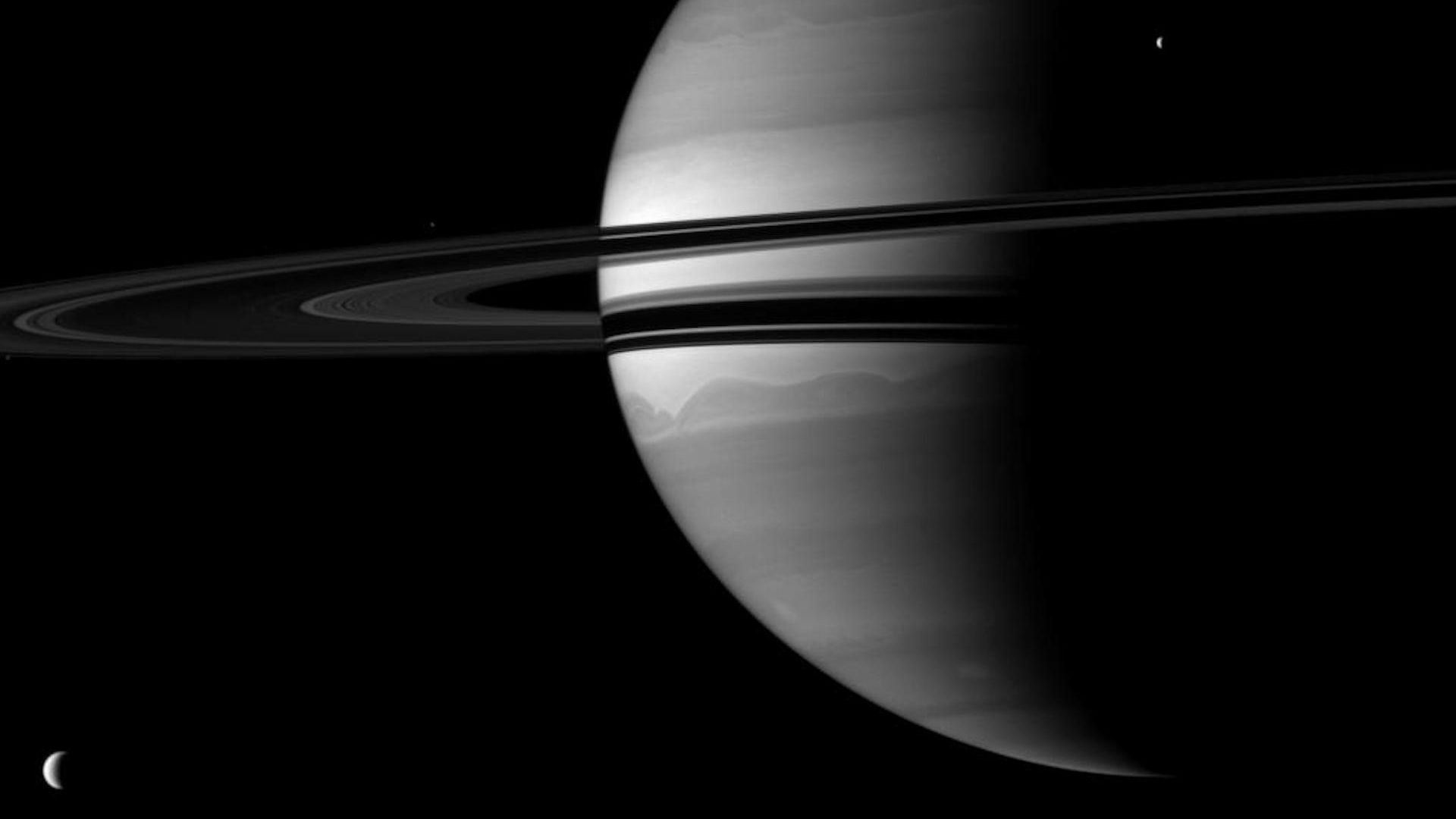

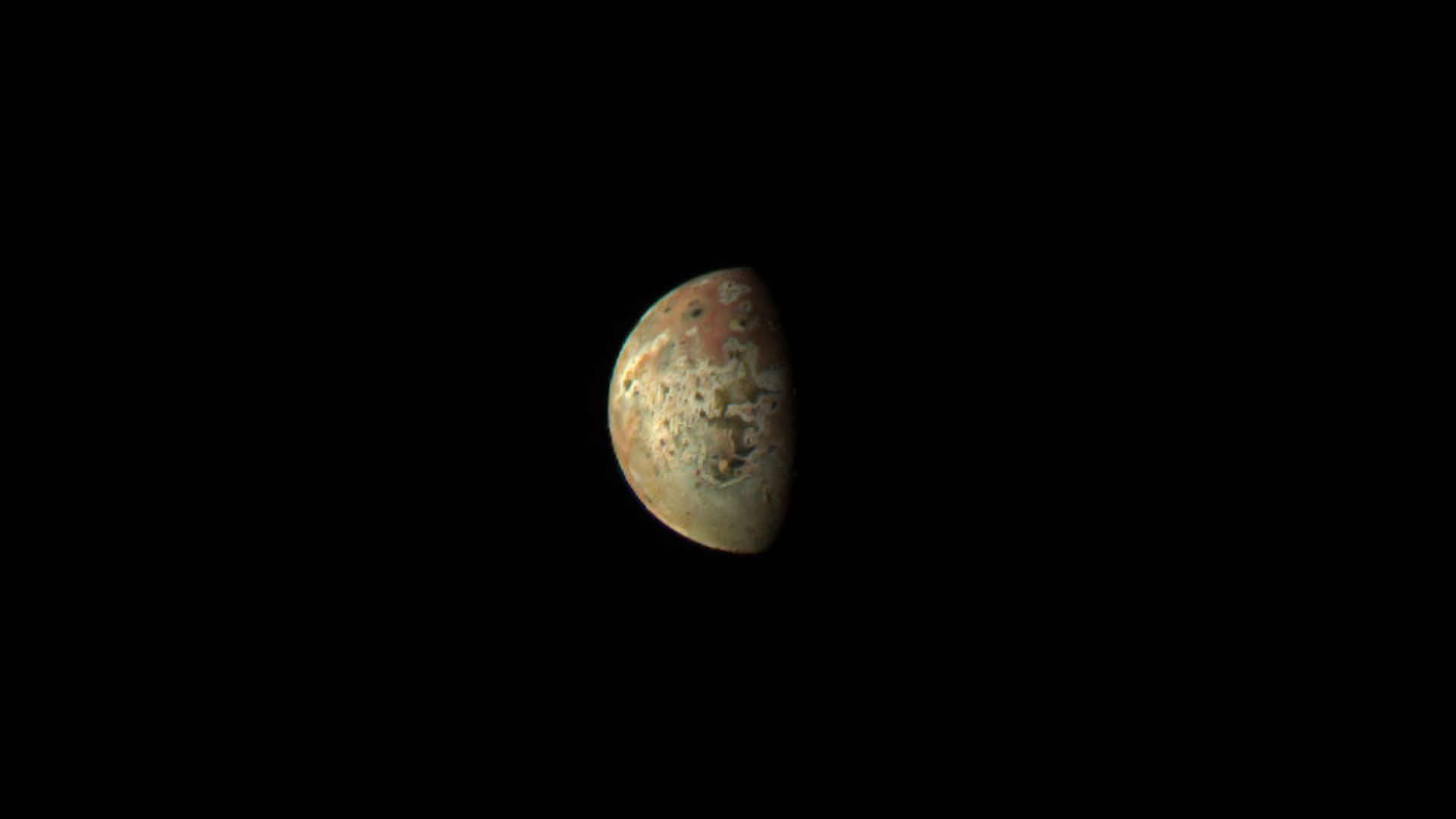

Learn more. | | | | | | 4. Out of this world reading list |  | | | Saturn's moon Titan in the lower left and Tethys in the upper right. Photo: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute | | | | 🇨🇳 China calls for space station commercial cargo proposals (Andrew Jones, SpaceNews) 🚀 SpaceX hires former NASA human spaceflight official to help with Starship (Michael Sheetz, CNBC) 👩🚀 SpaceX Axiom-2 private astronaut mission is "go" for May 21 launch (Mike Wall, Space.com) 🪐 Saturn shatters Jupiter's records for most known moons in the solar system (Kevin Hurler, Gizmodo) |     | | | | | | 5. Weekly dose of awe: Juno closes in on Io |  | | | Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS. Image processing: Kevin M. Gill (CC BY) | | | | The surface of Jupiter's Moon Io stands out in this photo taken by NASA's Juno spacecraft in March. - Juno flew just about 22,060 miles from Io today, making its closest-yet flyby of the volcanic moon.

- "Io is the most volcanic celestial body that we know of in our solar system," Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, said in a NASA statement.

- "By observing it over time on multiple passes, we can watch how the volcanoes vary — how often they erupt, how bright and hot they are, whether they are linked to a group or solo, and if the shape of the lava flow changes."

|     | | | | | | A message from the University of Central Florida | | K-12 students learn to grow produce in UCF's extraterrestrial soil | | |  | | | | Alongside NASA, University of Central Florida (UCF) researchers are challenging students to grow food in lunar and Martian dirt, teaching the first generation of farmers on the Moon and Mars. The national challenge is made possible using simulant regolith from UCF's Exolith Lab. Learn more. | | | | ⛓ Big thanks to Alison Snyder for editing and contributing, Sheryl Miller for copy editing, and the Axios visuals team. If this newsletter was forwarded to you, subscribe. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? Your essential communications — to staff, clients and other stakeholders — can have the same style. Axios HQ, a powerful platform, will help you do it. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

To stop receiving this newsletter, unsubscribe or manage your email preferences. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments