| | | | | | | | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Jul 20, 2023 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This edition focuses on the science and legacy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. It's 1,885 words, about a 7-minute read. - It's reported and written in collaboration with Axios space reporter Miriam Kramer, who is going to be the first on this team to finish the book "American Prometheus," which is the basis of Christopher Nolan's new biopic, "Oppenheimer."

- Send your feedback and ideas to me at alison@axios.com.

- This newsletter will be off next week and back in your inbox on Aug. 3.

| | | | | | 1 big thing: Oppenheimer revealed the human side of science |  | | | Photo illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios. Photos: Bettmann/Getty Images | | | | J. Robert Oppenheimer and the science he oversaw reshaped the world — but the political and cultural forces of the day also shaped the science he pursued, Miriam and I write. The big picture: In the abstract, science is often extolled as a search for truth untouched by politics and traveling on a separate track, but in practice science, politics, culture and society can strongly influence one another. Details: Oppenheimer described himself as indifferent to contemporary politics early in his career. - But that changed in the mid-1930s. Oppenheimer, whose parents were German and Jewish, developed a "smoldering fury" about the treatment of Jewish people in Nazi Germany.

- Politics helped push Oppenheimer into nuclear science — and it ultimately separated him from it when he was targeted during the Red Scare of the 1940s and 1950s for his opposition to the hydrogen bomb and stripped of his security clearance.

Zoom out: The Atomic Age encapsulates how political and cultural factors can shape science — what research gets funded, who funds it, who is in charge, and who gets to conduct the science. - "The type of science that gets done at any given time is itself a reflection of the times," says science historian Alex Wellerstein, a professor at Stevens Institute of Technology.

- "We know a lot about the bottom of the ocean and a lot less about difficulties that women have going through menopause," he says. "The Navy is interested in the former."

Between the lines: These factors can go beyond the funding and framing of scientific research, Wellerstein says. They can influence what conclusions are drawn. - The interplay of politics and science has been described by historians for decades but "there are a lot of forces who do not want that idea to be thought of — for good reasons and bad ones," he says.

- Acknowledging the political impact risks opening the door to any findings being subject to a political or cultural interpretation and for skepticism to slide into denialism.

The intrigue: The public's understanding of science and what shapes it is often influenced directly by those scientists who are best able to communicate their work. - Oppenheimer "was a scientist who could articulate a broad humanistic vision of the place of science within culture and politics. He was, in many ways, a general intellectual," says Charles Thorpe, a professor of sociology at the University of California San Diego.

Yes, but: Oppenheimer's experience underscored the potential dangers and challenges for scientists involved in policymaking. - "[T]he Oppenheimer case sent a warning to all scientists not to stand up in the political arena as public intellectuals," Kai Bird, co-author of "American Prometheus," wrote in the New York Times this week. "This was the real tragedy of Oppenheimer. What happened to him also damaged our ability as a society to debate honestly about scientific theory — the very foundation of our modern world."

- But, "[w]e actually benefit from the scientific community giving voice to policy ideas and engaging more actively," says Daniel Correa of the Federation of American Scientists.

- "[W]hether it's CRISPR and gene editing, nuclear weapons, or some facets of the AI debate — these are discussions where scientists need to be at the table" where policies are being made, Correa says.

The bottom line: The "relationship between science and politics is a two-way street," says Toshihiro Higuchi, a professor of history at Georgetown University who studies the environmental impacts of the nuclear age. - "It is not simply just politics always trumping science or science always prevails over politics."

- "Both are indispensable," he added.

|     | | | | | | 2. Inside a nuclear bomb |  Data: Axios research, NukeMap; Note: Diagrams are simplified for clarity; Graphic: Kavya Beheraj and Aïda Amer/Axios The Manhattan Project was responsible for developing two types of atomic bombs — named Little Boy and Fat Man — that were detonated above the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki respectively during World War II, Miriam and Axios data journalist Kavya Beheraj write. - They remain the only atomic bombs ever used in war.

- The bombs — first over Hiroshima and then over Nagasaki — killed tens of thousands of people when they were first detonated and many more died in the days and weeks that followed due to radiation poisoning.

By the numbers: Nine countries are known to have nuclear warheads today. - About 12,500 nuclear warheads total exist, according to an estimate from the Federation of American Scientists.

- The U.S. has about 5,244 nuclear warheads with about 1,536 of those retired, the FAS said in March.

- Russia is thought to have 5,889 nuclear warheads.

|     | | | | | | 3. Oppenheimer's science beyond the atomic bomb |  | | | Photo illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios. Photos: Bettmann/Getty Images | | | | Oppenheimer's scientific legacy stretches beyond his work as the "father of the atomic bomb," Miriam and I write. Details: Before overseeing the weapons lab at Los Alamos, Oppenheimer worked as a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, mentoring students, teaching and contributing to theoretical physics. - The development of quantum mechanics was just beginning and Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity was re-shaping the scientific world.

- "Almost all of his early papers are breaking new ground or clarifying an element of confusion in the community of scientists who were grappling at that time with a radically different conception technically ... and even philosophically than what came before," Los Alamos National Laboratory theoretical physicist Mark Paris tells Axios.

Between the lines: One of Oppenheimer's most important contributions to theoretical physics is still used today: the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. - The approximation helps give scientists a framework for attempting to solve the quantum many-body problem of predicting how three or more particles will interact.

- "Although he developed an approximate way of solving the problem, he did it in a way that could be systematically improved, and it's still with us today," Paris says.

The intrigue: Oppenheimer's intellect wasn't confined to just one part of theoretical physics. He puzzled over everything from quantum mechanics to astrophysics — and took a keen interest in experiments being conducted to answer fundamental questions in physics. - He predicted the existence of black holes and the positron.

- "One of the downsides of the way modern physics is done is we're constantly struggling against a fragmentary view of what theorists do and what experimentalists do," Paris said.

- Oppenheimer, however, had a "deep and abiding interest in what experimentalists were doing in the laboratory," Paris added.

|     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | The Axios Today podcast | | |  | | | | Catch up on the important news and interesting stories you won't hear anywhere else with host Niala Boodhoo. Each weekday morning, get the latest in everything from politics to space to race and justice. Listen now for free. | | | | | | 4. Trinity Test legacy in New Mexico |  | | | Tourists visit the Trinity Site, which is where the U.S. military detonated the world's first atom bomb in July of 1945, in the desert of New Mexico. Photo: Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images | | | | Oppenheimer's shadow still looms over New Mexico — as a scientific hero who helped reshape one of the nation's poorest states, and as a villain who generated a trail of human destruction still felt there today, Axios' Russell Contreras writes. Why it matters: Oppenheimer's reputation dominates discussions about the Manhattan Project, often pushing aside the stories and challenges of the New Mexicans affected by the atomic bomb tests. Details: Oppenheimer's influence in creating the unincorporated town of Los Alamos, New Mexico, helped lead to the establishment of the Los Alamos National Lab and other military industries in the state. - Those labs and industries have attracted top scientists from around the world to New Mexico, building a scientific hub and a thriving public school system.

- His reputation for his role in ending World War II and the mystery around the once-secret town of Los Alamos have sparked tourism around labs, test sites, the scientist's home and other places connected to Oppenheimer and the atomic bomb.

Yes, but: Oppenheimer isn't revered among some Hispanic residents and Mescalero Apache members, whose families lived near the site of the Trinity Test. During the Cold War, the U.S. government stepped up its production of nuclear weapons — something Oppenheimer opposed later in life — and began mining uranium across the Navajo Nation. State of play: New Mexico residents aren't included in the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act. - The federal law passed by Congress in 1990 awards financial reparations to Nevada Test Site downwinders and later uranium workers in other states.

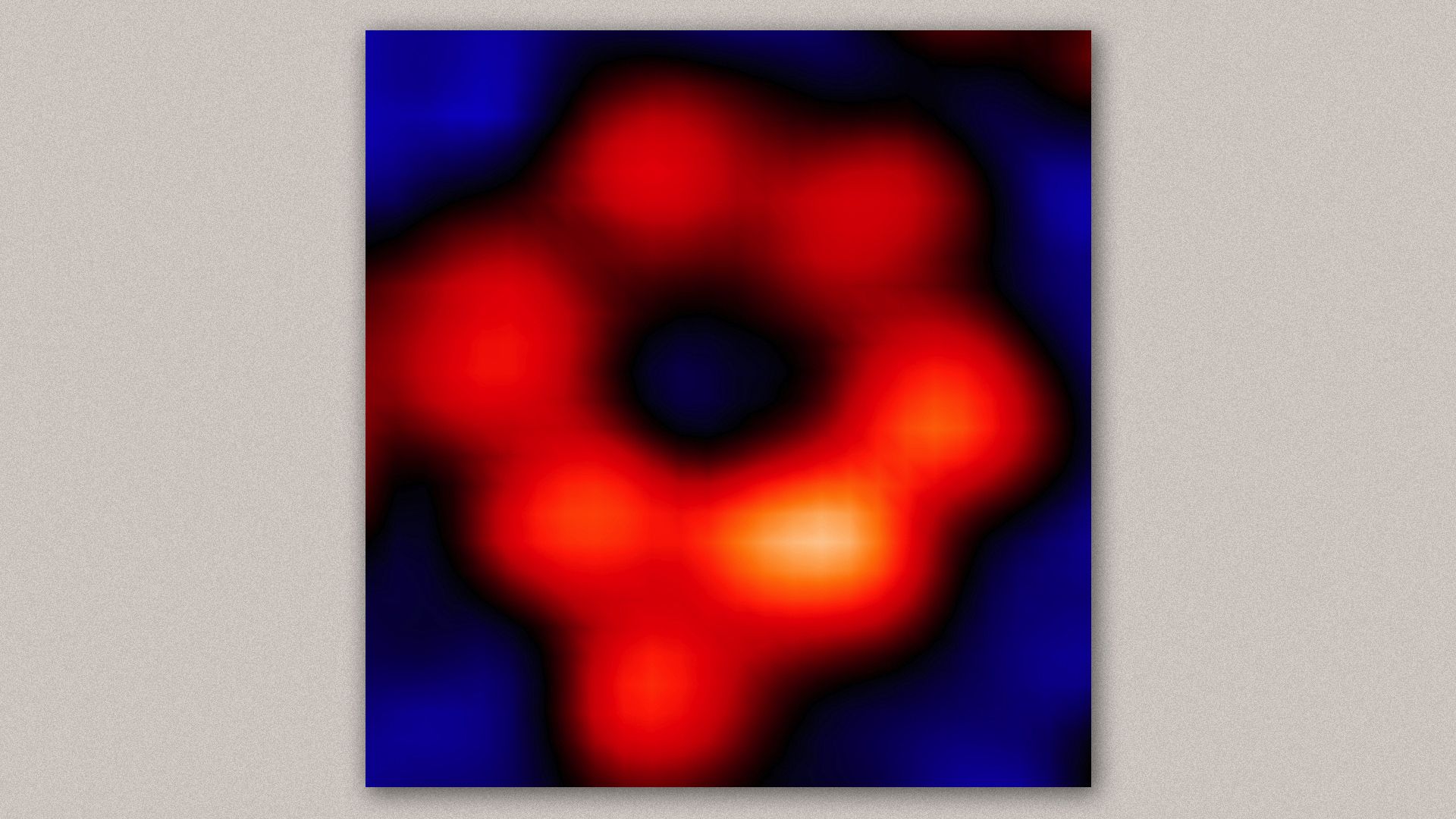

What to watch: U.S. Sen. Ben Ray Luján (D-NM) has reintroduced a bill to include New Mexico downwinders in RECA before its scheduled expiration in 2024. |     | | | | | | 5. Worthy of your time | | Stanford president resigns over manipulated research (Theo Baker — The Stanford Daily) 🎧 Quantum entanglement's long journey from "spooky" to law of nature (Adam Levy — Knowable) Centuries on, Newton's gravitational constant still can't be pinned down (James R. Riordon — Science News) |     | | | | | | 6. In their words |  | | | Photo illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios. Photos: Hulton Archive and Keystone, MPI via Getty Images | | | | "We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent." — J. Robert Oppenheimer speaking about the Trinity Test "Scientists have an important role to play in the creation of conditions for a secure and peaceful world, but I do not believe that scientists alone can achieve the goal." — Linus Pauling, chemist who won the Nobel Prize for chemistry and later the Nobel Peace Prize for his activism opposing the nuclear arms race "As a firsthand witness to this atrocity, my only desire is to live a full life, hopefully in a world where people are kind to each other, and to themselves." — Yasujiro Tanaka, survivor of the Nagasaki bombing to Time magazine |     | | | | | | 7. Something wondrous |  | | | An image of a ring-shaped supramolecule where only one iron atom is present in the entire ring. Credit: Saw-Wai Hla/Ohio University and Argonne National Laboratory | | | | Scientists recently reported taking the first X-ray image of a single atom. Why it matters: Single atoms can be seen and manipulated but until now there wasn't a way to identify the element an individual atom is made of. - Saw-Wai Hla, a physicist at Ohio University and Argonne National Laboratory, has been working for 12 years on a technique for "fingerprinting" individual atoms.

- "This is the dream of the scientist, to get down to one atom, and we made it," he says.

How it works: The information Hla and other researchers are after — what element an atom is made of, its chemical state, and its magnetic spin — is determined from electrons orbiting close to the nucleus. - The energy required to knock an electron from its inner orbit and leave an atom is different for each element.

- To detect that signature, the researchers looked to the scanning tunneling microscope, which positions a sharp needle, or tip, less than 1 nanometer above a surface. As the tip moves across the surface, a current is applied and electrons tunnel between the tip and the surface. Changes in that current as the tip moves are then used to create an image.

- Hla and his colleagues used a similar technique, but with X-rays. The energy of the X-ray beams is changed as the tip moves across the surface and when it hits the exact right energy, the "electron will escape and we can detect it with that tip," he says.

- They described their technique in the journal Nature in May.

What to watch: Hla says the ability to detect the properties of one atom could eventually open up the possibility of detecting elements in the environment, designing novel materials by controlling atoms and manipulating them for quantum computation. - The latter would require determining the magnetic state of an atom, which the researchers are now working on.

The big picture: Researchers are carrying on the legacy and findings of the atomic age, Hla says. "We are all linked." |     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | The Axios Today podcast | | |  | | | | Catch up on the important news and interesting stories you won't hear anywhere else with host Niala Boodhoo. Each weekday morning, get the latest in everything from politics to space to race and justice. Listen now for free. | | | | Big thanks to editor Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath, reporters Russ Contreras and Miriam Kramer, data journalist Kavya Beheraj, visuals editor Aïda Amer and copy editor Carolyn DiPaolo. Sign up here to receive this newsletter. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? Your essential communications — to staff, clients and other stakeholders — can have the same style. Axios HQ, a powerful platform, will help you do it. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

To stop receiving this newsletter, unsubscribe or manage your email preferences. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments