health tech

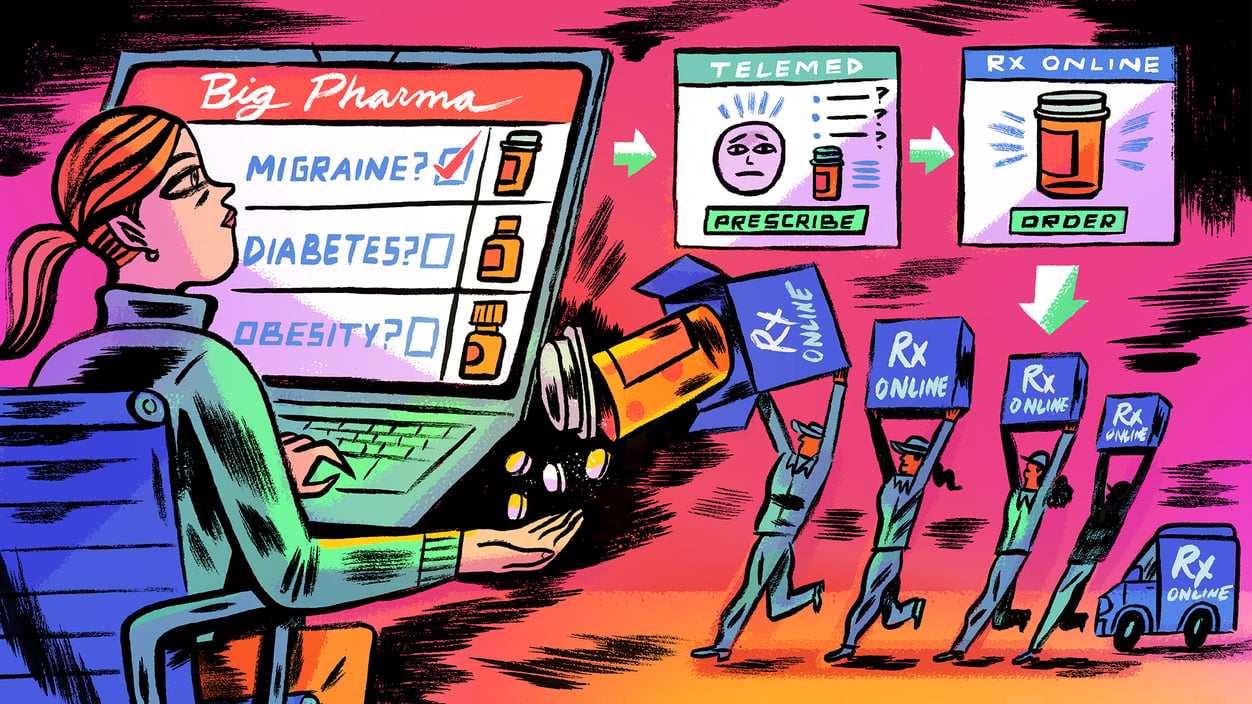

Big pharma wants in on the fast-growing online prescription market

Mike Reddy for STAT

Eli Lilly and other drug makers broke new ground with their phenomenally popular weight-loss drugs. Now Lilly has also caught another new wave. Earlier this month it launched a platform for patients to find and fill prescription for its drugs — including Zepbound and beyond — online. Patients can go to LillyDirect, choose a pipeline for their condition, and then follow a route to a telehealth site for a prescription that online pharmacy Truepill will deliver.

This might sound like the "talk to a doctor now" approach smaller companies have taken, but Lilly's is the most robust digital offering in this space yet, STAT's Katie Palmer reports. Pfizer and AbbVie are also directing patients to telehealth. "It's really clever in terms of increasing prescribing," Steven Woloshin of the Center for Medicine and Media at The Dartmouth Institute told her. "Whether it's increasing appropriate prescribing, that's really an open question." Read more.

infectious disease

New study helps unravel why it has been so difficult to develop a staph vaccine

Staphylococcus aureus is one the most common bacteria you'll find on the human body, where it is usually an innocuous resident in your nose or on skin. In some cases, however, this common commensal moonlights as a deadly pathogen. Antibiotic-resistant staph infections cause about 320,000 hospitalizations and more than 10,000 deaths a year. But despite researchers' best efforts, dozens of experimental vaccines that showed promise in mice later failed in clinical trials, STAT's Jonathan Wosen tells us.

A new study led by scientists at the University of California, San Diego helps unravel why. Unlike humans, lab mice are rarely exposed to staph. And while the researchers, who tested several vaccines, found that immunizing mice that had never been exposed to staph produced a protective response, they also showed that inoculating animals that had previously been infected did not. That's because the antibodies the animals produced in response to infection actually hampered their vaccine responses. There were some notable exceptions. Vaccines that targeted parts of the bacteria that didn't elicit strong immune responses during natural infection worked well.

"It kind of defies the rules for how you make a vaccine," said George Liu, an infectious disease expert at UCSD and the study's senior author. He hopes to test whether the same rule reversal applies to other microbes, such as those responsible for malaria and tuberculosis. The recent findings, published yesterday in Cell Reports Medicine, build on a previous study published by Liu's group that focused on a single failed vaccine developed by Merck. Liu is hopeful his team's mouse model could more reliably predict whether future vaccines work in people.

closer look

In mice, a potential way to stem hair loss from chemo

Adobe

Adobe

Gotta love serendipity in science, when some chance observation sparks an insight that could lead to important change. You know the story of penicillin's discovery, when Alexander Fleming noticed bacteria weren't growing near this unknown mold in a dish. Maybe something like that was going on when self-described "bad grad student" Jessica Shannon noticed mice she didn't euthanize right away after an inconclusive experiment were hairier than expected when she checked on them later.

She'd injected them with a cytokine called thymic stromal lymphopoietin, or TSLP, hoping but failing to improve skin healing. But now, blocking the TSLP receptor in hair follicles is being tested to see if it can prevent hair loss typical in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Perseus Therapeutics, a biotech founded last year, is currently developing an antibody to do this, providing an alternative to the dreaded "cold cap" patients can now try. STAT's Angus Chen explains the long road ahead.

No comments