closer look

A medical student sees diversity's promise, and how far away the reality is

Adobe

Health care is hardly immune from the backlash against efforts to advance diversity, equity, and inclusion, whether it's legislation in Florida or litigation in California, medical student David Velasquez notes at the beginning of his STAT First Opinion. He cites chilling statistics on stubbornly poor health outcomes for Black people compared to white people. And he shares an encounter with a patient whose language he spoke, a familiarity that led a surgeon to believe he was her family member, not his colleague.

"Within the space of an hour, I saw the promise of diversity, equity, and inclusion, a powerful connection that transcends barriers erected by the meeting of two strangers, and then I saw the critical gaps it has yet to fill: a diverse workforce with the ability to understand unconscious biases and navigate differences between individuals," he writes. "I saw just how much diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts are necessary for patients like Laura and clinicians like myself." Read more.

health equity

1 in 3 LGBT people cites poor treatment in health care

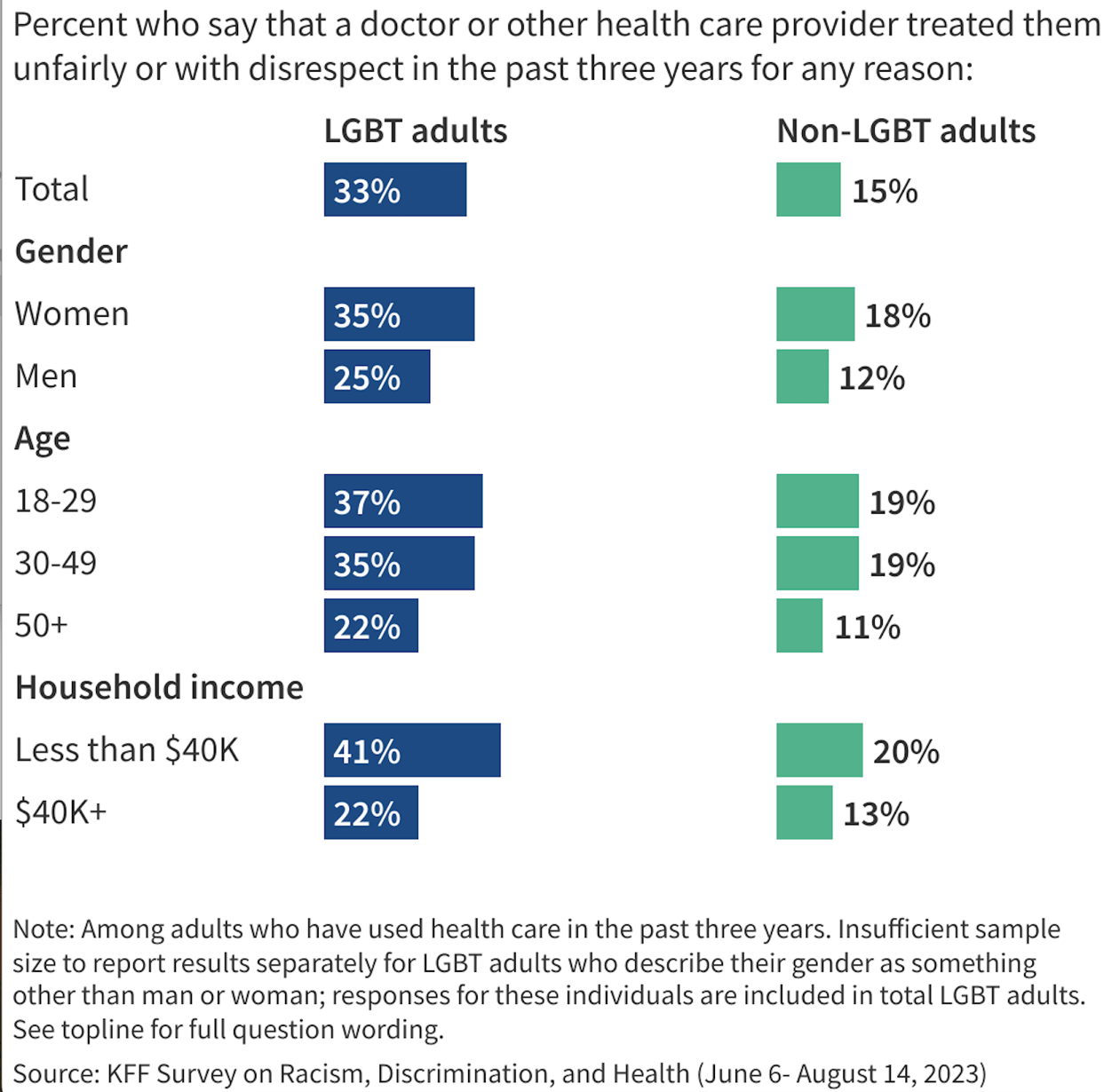

One-third of LGBT adults say they were treated unfairly or with disrespect by a health care provider over the last three years, a new KFF survey tells us, a level more than twice as high as people who don't identify as LGBT. The rates of such negative experiences among Black and Hispanic LGBT adults were higher than among white LGBT adults. As a result, many survey respondents said they were less likely to seek care (39%), more likely to find a new provider (36%), or say their health deteriorated (24%).

Asked about their mental health, 39% of LGBT adults say it was "fair" or "poor," with rates higher among younger LGBT adults. Overall, about half report feeling anxious either "always" or "often" in the past year; a third felt lonely or depressed at least "often," about double what non-LGBT adults say.

cancer

When is too old for a follow-up colonoscopy?

Much of the attention paid recently to colorectal cancer has focused on the alarming rise in rates among younger people, prompting recommendations to start screening at an earlier age. A new study in JAMA Network Open looked at the other end of the age spectrum, asking when surveillance colonoscopies — tests for cancer after precursors known as adenomas or neoplasias were found — can end.

In their cross-sectional study, the researchers analyzed records from nearly 10,000 patients age 70 to 85 who'd had precancerous growths removed a year or more before. In their surveillance colonoscopies, cancer detection was rare, found in 0.3% of patients, while advanced neoplasia was more common (12%), especially among people who'd had advanced growths removed before. The authors recommend discussing any benefits of continued testing "in the context of the life expectancy of the patient and weighed against the rare but known harms of colonoscopy, which increase with advancing age and comorbidities."

No comments