first opinion

Measles could come back, but her sister can't

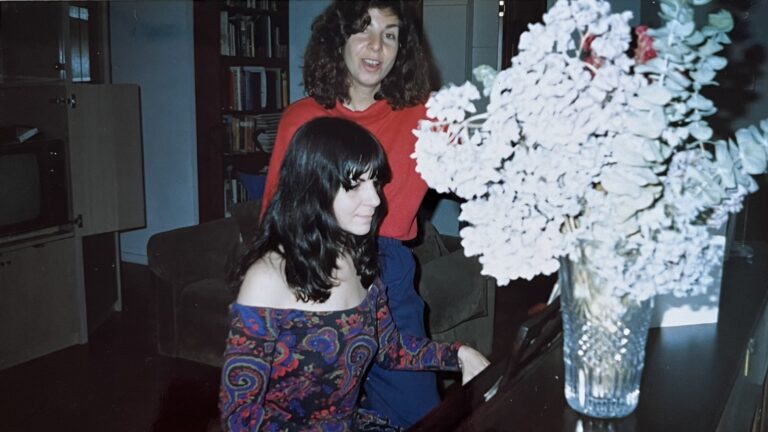

COURTESY EMMI S. HERMAN

It was February of 1960 when Emmi Herman's sister Marcie — "healthy, precocious" — caught measles from a fourth grade classmate. The viral infection quickly developed into measles encephalitis, a rare form of the disease that can cause permanent brain damage. Marcie made it home from the hospital eventually, Herman recalls, but she was never the same.

Measles is now a preventable disease, declared "eliminated" in the U.S. at the turn of the century thanks to a vaccine. But in just the first four months of this year, there were more than double the number of measles cases than in all of last year. Why? "Fewer parents are vaccinating their children against measles, their decision most often prompted by social media disinformation," Herman writes. "They should have met my sister," who died in 2020 from Covid complications after living for decades with physical and psychological impairments. Read more in Herman's touching First Opinion essay.

abortion

Pre-Dobbs abortion restrictions tied to more murders of women and girls, study shows

Before Dobbs ushered in a wave of abortion restriction laws, some states limited access by targeting the regulation of abortion providers. In a study published yesterday in Health Affairs, researchers analyzed CDC data on violent deaths and so-called TRAP laws — like mandating physicians have admitting privileges at a local hospital or specifying the width of corridors at a clinic — and found that the laws were associated with higher murder rates for women and girls.

Between 2014 and 2020, enforcement of each additional law was associated with a 4.4% increase in total murders of women and girls aged 10 to 44, and a 3.4% increase in the rate of those related to intimate partner violence. It's unclear whether the association is driven by the laws or other factors in the states where they were enforced. But overall, the findings complement previous research that has found people denied an abortion were more likely to experience violence from their partner than people who got a wanted abortion.

addiction

FDA stands by its decision to approve controversial DNA test for opioid addiction risk

Last month, a group of prominent geneticists, public health researchers, and experts in addiction and device regulation urged the FDA to revoke the recent approval of a DNA test called AvertD. Together they argued that the physician-ordered test, intended to help guide doctors' opioid-prescribing decisions by predicting an individual's genetic risk of opioid addiction, lacks a firm scientific foundation.

In a letter dated May 2, the FDA responded to the group, acknowledging their concerns, STAT's Megan Molteni reports. But the regulator maintained its stance that the test's required "black box" warning, along with a post-market study of the test's performance, should be enough to alleviate their worries. Michael Abrams, of Public Citizen's Health Research Group, told Molteni the letter did not substantively address the group's concerns about the test's validity: "This decision continues to seem like brash, fast-track approval," he said.

kudos corner

STAT's Bob Ross is a Pulitzer Prize finalist for "Denied by AI" investigation

STAT reporters Casey Ross and Bob Herman (a duo who, real ones already know, we affectionately call "Bob Ross" here in the newsroom) were named finalists for the 2024 Pulitzer Prize in the investigative reporting category for their series "Denied by AI," which uncovered how UnitedHealth Group, owner of one of the largest health insurers in the U.S., used an algorithm to deny needed care to seniors.

When I asked Casey if there's a detail from the stories that stands out to him now, he recalled a phone call between a NaviHealth care coordinator and a woman named Gloria Bent. Bent's husband had just undergone brain surgery to remove a cancerous lesion and was paralyzed on the left side of his body. "Did NaviHealth — UnitedHealth's subsidiary — call to offer support, to help her, to make sure she had the resources she needed? No," Casey wrote to me. "It called at the behest of an algorithm to tell her to get her affairs in order and retrofit her home within two weeks — because that's when payment for her husband's care would be cut off."

You can expect Casey and Bob to stay on the case. "The financial incentive still exists to use AI to deny care," Casey wrote. "Billions and billions of dollars are at stake here, and loosely regulated algorithms will be used to chase after it until lawmakers, or courts, take action to stop them." Read more from their multi-part series.

No comments