stat investigation

Can changing one algorithm fix everything?

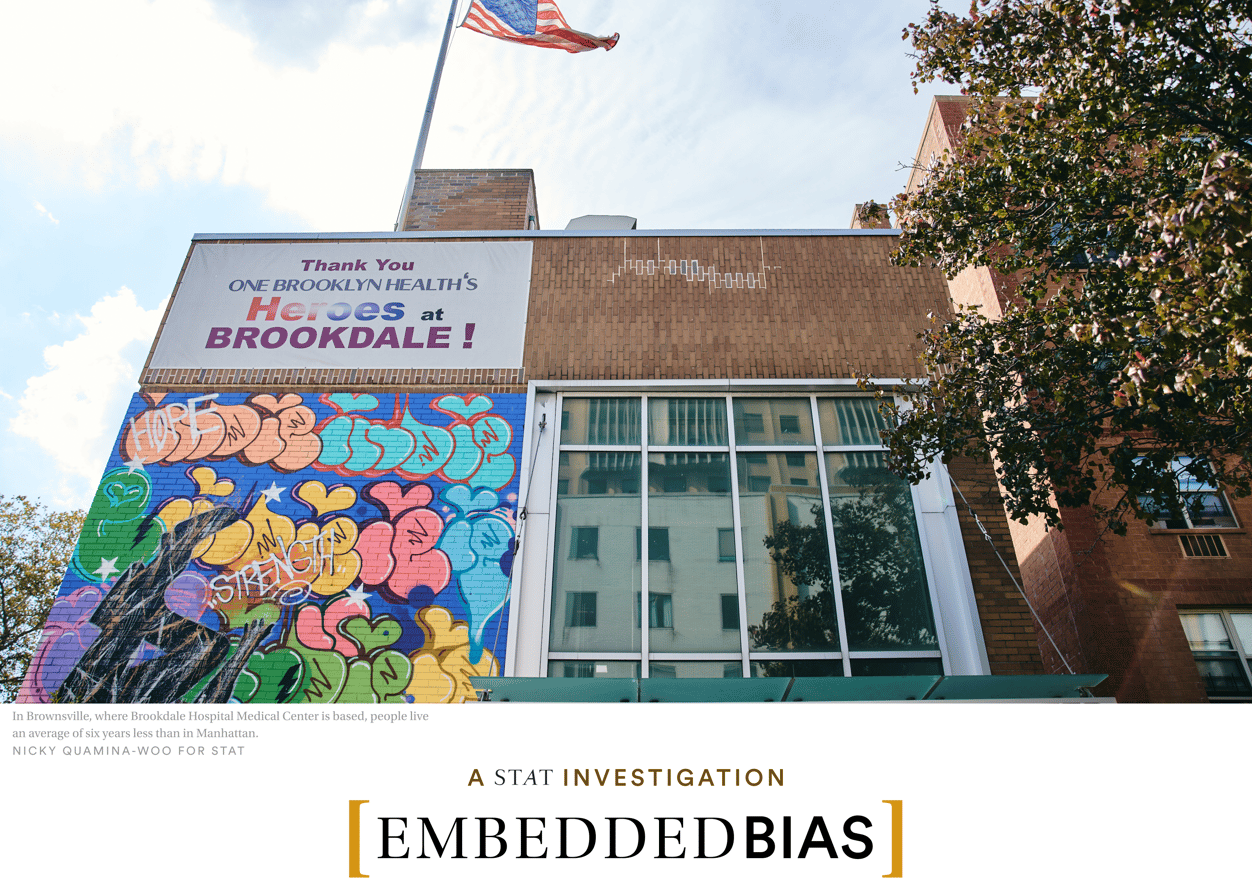

Chronic kidney disease is an epidemic in Central Brooklyn. The service area for One Brooklyn Health, a safety net hospital system serving some of New York's poorest and sickest patients, contains 350,000 or more people who could benefit from kidney care. But often people don't reach the clinic doors until it's much too late. OBH, which serves a mostly Black population insured by Medicaid or Medicare, is currently treating fewer than 2,000 patients for kidney disease.

If it sounds like this would be exactly the place to benefit most from removing race from the calculations that assess kidney disease, which can help expand the pool of patients who have access to earlier care — the hospital thought of that, too. The leaders of OBH were early adopters in the movement to eliminate race from the commonly used equation that estimates kidney function. But one updated equation can't fix everything.

"It doesn't change the realities on the ground," nephrologist Puneet Bedi told STAT's Usha Lee McFarling. People can't always get child care or transportation to go to the doctor. When someone is struggling to pay rent, health care takes a back seat. "We have corrected the equation but it has very little impact on health outcomes."

Read more from Usha on how one hospital system is working to stem the racial disparities that run through American kidney care.

transplants

The first face and eye transplant

Yesterday, researchers in JAMA reported the results of the first whole eye and face transplant. The surgeons were able to get blood to reach the eye, a big hurdle to helping someone regain vision in the transplanted organ, but they were not able to fully restore vision. STAT's Anil Oza caught up with Daniel Ceradini, the lead author of the study and a plastic surgeon at NYU Langone Health.

What was the story behind this transplant?

We performed, now, four face transplants at NYU, this last one incorporating an eye. The eye had always been talked about as being "The Holy Grail of vision restoration," but it never had been attempted successfully in the past. So this is the first report of that actually happening. The report details Aaron, who sustained an electrical injury while working, who needed both parts of his face [missing word?] as well as an eye to restore his facial aesthetics, his function, and his quality of life.

What does this mean for future eye transplants?

The hurdles that we have to overcome are optic nerve regeneration, for one. Preventing the optic nerve from dying from ischemic injury [when blood flow is cut off] during the transplant would be another. We don't actually know how the connections between the regrowing optic nerve and the brain will occur. That's just something that's never been studied. There's no real human precedent set for it.

video

What do the Karate Kid and drug patents have in common?

.jpg?width=1252&height=704&upscale=true&name=paytodelay_FULL%20(0-01-17-09).jpg) Anna Yeo/STAT

Anna Yeo/STAT

To find out, watch the latest video in the Behind the Counter series from STAT's Anna Yeo. In her last video, Anna explains how drug patents last for 20 years. But it wasn't always that way: Before 1984 (hint!), those companies didn't really have a full 20 years of patent protection. They had 20 years from the date the patent was issued, but some of that time was sucked up performing clinical trials and working toward FDA approval before a drug could actually be sold. Meanwhile, generic drugmakers couldn't access a drug's formula until the original patent expired. Then, they had to conduct their own clinical trials, delaying the entrance of generics onto the market.

Then came the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, in which legislators worked to find a balance (another hint!) that afforded both parties some protections. Watch Anna's video to learn more.

No comments