policy

Telehealth companies working with Pfizer and Lilly draw scrutiny

Senators are again questioning the financial relationship between pharma giants Eli Lilly and Pfizer and the telehealth companies they link to from direct-to-consumer portals LillyDirect and PfizerForAll. In letters sent to UpScript Health, Form Health, 9amHealth, Thirty Madison's Cove, and Populus Health, Sen. Dick Durbin and three other lawmakers asked for detailed information about prescription volumes and possible provider incentives, aiming to determine if contracts could run afoul of the federal anti-kickback statute.

Pfizer and Eli Lilly, in response to similar questions from the senators in October, said that providers are not encouraged or incentivized to prescribe specific drugs, as the telehealth platforms have also said. In her new story, Katie Palmer writes that despite the scrutiny, the drug giants are only increasing their commitment to their online platforms with new direct-to- consumer offerings.

Read more here

Medical devices

Study finds chronic late reporting of device problems

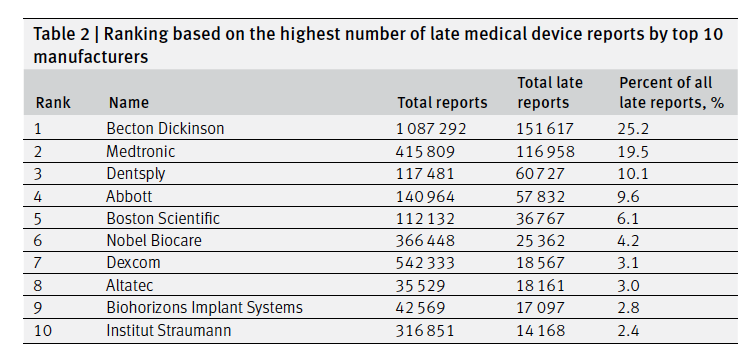

In a new study in the BMJ, researchers analyzed the Food and Drug Administration database where manufactures report adverse events and found that a huge number of reports come in late. Manufacturers are required to report issues within 30 days of finding out about them. Of 4.4 million manufacturer reports between 2019 and 2022, about 600,000, or nearly 14% came in late. Over 600,000 came in with missing or invalid dates. Notably, 1,004 deaths were reported late. The authors tease out a number of interesting nuances to how reporting happens. For example, late reports were disproportionately released in batches by manufacturers, which the authors suggest "could stem from manufacturers knowingly withholding important safety information from the public." The authors also concede it might just take time to verify reports. They also name the top 10 late reporters (see above).

Most medical devices in the United States come to market with limited clinical data, and device surveillance is viewed as a key way to keep patients safe. But the FDA's system for collecting data and keeping tabs on medical devices on the market has been shown to fall short, for example in the case of Philips' faulty CPAP machines.

business A few details from Hinge's IPO filing

Earlier this week, virtual musculoskeletal care company Hinge Health announced its plans to go public. I spent some time looking at the filing, and two things jumped out at me.

Medicare

Hinge primarily sells its services to self-insured employers, or companies that pay the cost of their workers' health care. Throughout the filing, Hinge repeatedly notes its goal of expanding to Medicare Advantage and even to Medicare and Medicaid, pointing to the potential multi-billion dollar market opportunity. The company notes that it is in the early stages of expanding to MA and that its pelvic health and fall prevention programs are being used in MA. Hinge also says that it managed to parlay success with partners that work with some of its customers into deals for their MA populations.

All-in on automation

It shouldn't be all that surprising that a tech company in 2025 is making a big deal about the opportunity for automation. Even then, I was struck by Hinge's estimate that, "based on data from 2024, our platform reduced the number of human care team hours associated with traditional physical therapy by approximately 95%." Ways Hinge accomplishes this include using a computer vision system to supervise exercise sessions and using AI to support care teams. Their aggressive stance on automation reminds me very much of what Virgílio Bento, CEO of Sword, a Hinge competitor, told me a few weeks ago about his own vision for "AI care."

No comments