the maha diagnosis

Experts say this RFK Jr. idea could be a good one

Alex Hogan/STAT

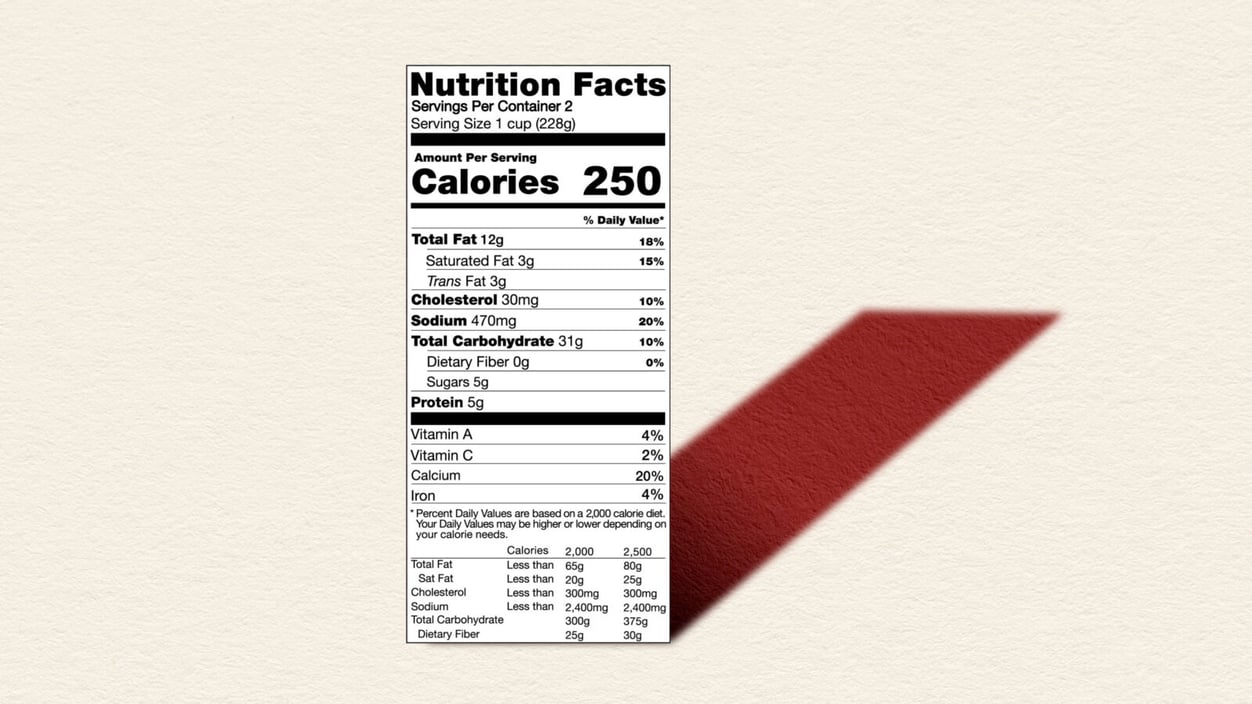

Fewer than a third of medical students in the U.S. receive the recommended minimum of 25 hours of nutrition education, and more than half report receiving no formal education on the topic at all. Kennedy wants that to change: "One of the things we're gonna do at NIH is to really give a carrot and stick to medical schools across the country saying you gotta put in your first-year curriculum a really good, robust nutrition course," he said in an Instagram video earlier this month.

While the specifics of this plan are unclear, the general goal is one that nutrition and food policy experts have been calling for for years, STAT's Sarah Todd reports. And some people even see enhanced nutrition education as a way to combat the bias against higher-weight patients that's entrenched in the medical profession. Read more from Sarah on the potential benefits.

one big number

7,000

That's how many daily steps are needed in order to achieve clinically meaningful improvements in certain health outcomes, including mortality, as compared to 2,000 steps. That's according to a systematic review, published yesterday in The Lancet Public Health, that analyzed data from 57 studies on step counts and health outcomes. With 7,000 daily steps, study participants saw a 47% lower risk of both all-cause mortality and of dying from cardiovascular disease, a 25% lower risk of getting cardiovascular disease, a 14% lower risk of type 2 diabetes, a 38% lower risk of dementia, and more.

While evidence on the utility of counting steps has historically been limited, the authors find that it's been rapidly increasing over the past decade. They believe that daily steps are a practical metric for physical activity guidelines and recommendations. Even 4,000 daily steps, they found, could improve outcomes as compared to 2,000.

infectious disease

Most U.S. bird flu cases have been mild so far. Why?

The H5N1 bird flu virus has historically extracted a heavy toll when it infects humans, with nearly half of confirmed cases ending in death over the past three decades. But only a single death has occurred out of the 70 cases reported in the U.S. over the past year and a half, leaving experts puzzled. A new study adds weight to an argument that the immunity people have developed to the virus that caused the most recent flu pandemic (an H1N1 virus from 2009) has induced some cross-protection that may make it harder for H5N1 to infect people, and mitigating the disease severity when it does.

Helen Branswell, who has been reporting on H5N1 bird flu for 20 years, covered the study. And while all of the outside experts she spoke to described the paper in glowing terms, not everyone is convinced by this argument. Read more from Helen on what outside experts had to say — and the one assumption that everybody agreed would be unwise to make.

No comments