Closer Look

Under fire: A blood test to detect cancer from microbial signatures tied to tumors

Buzz has been building for blood tests to detect serious diseases, from Alzheimer's to cancer. There's been some controversy, too, about how they work and what Medicare will cover, but nothing like this week's firestorm over a proposed blood test for cancer based on the microbiome. A 2020 Nature paper suggested microbes that colonize tumors create such specific signatures they could identify cancer types with near-perfect accuracy. The startup Micronoma was founded on this idea.

On Monday, other researchers published a manuscript on the preprint site bioRxiv (and then tweeted) that they'd found two "fatal errors" in the original paper. The argument turns on whether human DNA was filtered out and false associations made between microbes and cancer. The Nature authors refuted this on GitHub. STAT's Angus Chen and Matthew Herper sort out the arguments about a test that could revolutionize cancer screening and early detection — if it works.

medicine

Clinical fields with more women and people of color paid the least

STAT's Usha Lee McFarling brings this report: An analysis of nearly 800,000 medical trainees published yesterday in JAMA found that specialties with the most trainees who were women or from groups underrepresented in medicine earned the least in jobs in academic medicine. The highest paychecks went to those in surgical specialties, which had the least racial and gender diversity.

The authors found the biggest gap in pay between general pediatrics, where an assistant professor earned $200,860 and a full professor earned $641,300, and neurosurgery, where an assistant professor earned $278,300 and a full professor earned $831,900 annually. The authors suggest that more investigation is needed to understand the discrimination, attrition, and "specialty culture" that may be impeding more diversity in higher-paying fields.

obesity

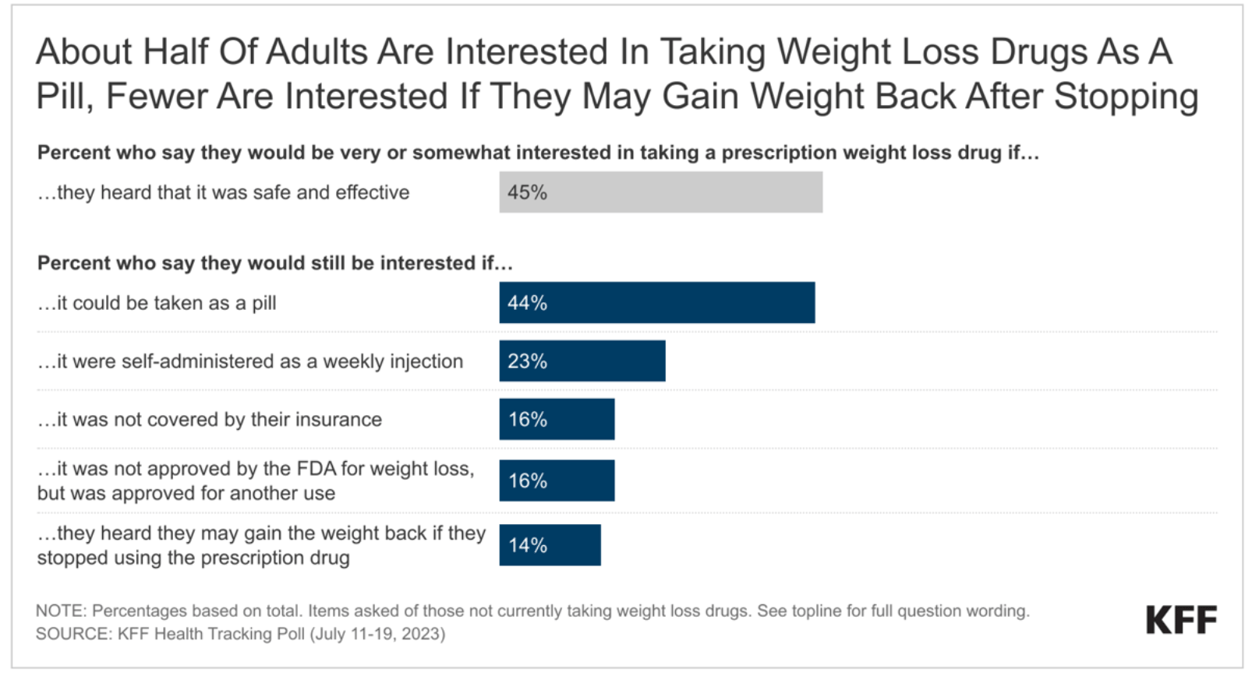

Americans say weight loss drugs sound good until they get to the fine print

The new weight loss drugs are popular, but only up to a point. A new KFF poll out today says 59% of Americans would be interested in a safe and effective weight-loss drug and 45% are interested in the medications even if they want to lose just a few pounds. But when they hear some caveats, interest falls:

- To 16% if health insurance wouldn't cover their cost.

- To 16% if the FDA doesn't approve the drugs specifically for weight loss.

- To 14% if they might regain lost weight when they stop taking it.

Asked whether insurers should cover weight loss drugs, 80% say they should for people who have obesity or overweight, 53% say they should for anyone who wants to lose weight, and 50% say they should even if that meant higher premiums for everyone.

Separately, despite the D.C. furor, only one-quarter of people know the Inflation Reduction Act allows Medicare to negotiate some drug prices.

No comments