| | | | | | | | | | | Axios Science | | By Alison Snyder · Aug 03, 2023 | | Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,751 words, about a 6½-minute read. - Send your feedback and ideas to me at alison@axios.com.

- We'll be off next week and back in your inbox on Aug. 17.

| | | | | | 1 big thing: A science agreement caught in crosshairs |  | | | Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios | | | | A 44-year-old agreement that established a framework for the U.S. and China to cooperate on scientific research is set to expire at the end of this month — putting a longstanding pillar of relations between the two countries in question. Why it matters: Whether the agreement — the first signed between the U.S. and China when they normalized relations in the late 1970s — is renewed, reworked or left to expire will send a signal to Beijing. Politicians and practitioners are now debating what exactly that message should be. - The U.S.-China Science and Technology Agreement (STA), originally signed in 1979 and renewed about every five years with the last time being in 2018, opened the door for scientists to collaborate in physics, chemistry, health and other areas. Cooperation between the countries helped China to transition from ozone-depleting CFCs and enabled the sharing of influenza data used to devise yearly vaccines.

- More than four decades into the agreement that spanned a pandemic and several administrations of fiery rhetoric, the broader nature of that cooperation is being scrutinized over concerns about Beijing-backed intellectual property theft and the Chinese military benefitting from knowledge about U.S. scientific advances.

- Supporters of renewing the STA in some form argue the benefits of cooperation outweigh those risks. Opponents say continuing the agreement signals to Beijing that the U.S. doesn't hold serious concerns about the risks.

Details: The STA signing gave "a form of permission for lab-to-lab, university-to-university, scientist-to-scientist cooperation," says John Holdren, former director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) during the Obama administration. "It legitimized the whole notion that collaboration was respectable." - Increased collaboration has helped to build personal relationships between U.S. and Chinese scientists, many of who went on to become senior officials in Beijing and Washington and leveraged those relationships to tackle science-based issues of mutual interest, he says.

- Scientific collaboration between the U.S. and China came under intense scrutiny during the Trump administration, when the U.S. Justice Department launched the China Initiative to investigate possible Chinese intellectual property theft and espionage. The program was shuttered after allegations officials racially profiled scientists, and cases fell apart.

- The STA — and under its umbrella federal research agencies' agreements with their Chinese counterparts — is nonbinding but facilitated data sharing about satellites, climate and seismic activities, as well as fusion and subatomic particle experiments.

- Research programs, projects, centers, meetings and exchanges across the fields of chemistry, physics, climate and energy science, agriculture, health and others were organized in federal U.S. agencies.

The agreement also carries a lot of symbolism, and recognized cooperation could "strengthen friendly relations" and "promote the well-being and prosperity of both counties." - In 1979, China lagged far behind the U.S. in scientific and technological capabilities.

- "It was unimaginable to think of where China was in terms of science and tech then versus where they are now," says Scott Michael Moore, director of China Programs and Strategic Initiatives at the University of Pennsylvania. "[T]here was no contemplation of any kind of rivalry and IP issues weren't on the radar."

What they're saying: The House Select Committee on China in a June letter to Secretary of State Antony Blinken said it would "strongly recommend" the U.S. not renew the STA, citing concerns that research under the STA could strengthen China's military-industrial complex. - Kim Montgomery, director of International Affairs and Science Diplomacy at the American Association of the Advancement of Science, acknowledges, "there are legitimate concerns about national security, intellectual property and competitiveness to name a few but those call for modifications to the agreement and not walking away."

The other side: Chinese ambassador to the U.S. Xie Feng said at the Aspen Security Summit last month that renewal of the agreement is a priority for U.S.-China cooperation. Between the lines: Several senior U.S. officials have traveled to China since June as the Biden administration tries to reduce tensions between Washington and Beijing. - Not renewing the agreement could complicate those efforts.

|     | | | | | | 2. Higher temperature (and drama) physics |  | | | Illustration: Annelise Capossela/Axios | | | | Late last month a team of scientists claimed they'd developed a material that could act as a superconductor at room temperature — a holy grail of physics. Excitement and skepticism ensued, and for more than a week researchers around the world have been attempting to replicate the results. Why it matters: Superconductors that can operate at room temperature and ambient pressure hold promise for quantum computing, a more efficient energy grid, producing energy from fusion and more. How it works: Superconducting materials can conduct electricity without losing energy in the form of heat, which happens as electrons move through a material and interact with atoms. Today's superconductors — for example, the magnets used in MRI machines — require ultra-cold temperatures to operate. - 'There's no physics reason it can't work," says Andrew Cote, an engineer who has worked on superconductors for particle accelerators and fusion energy, and is chronicling the developments in real-time on social media.

- It is a materials science problem that researchers have long tried to solve, with instances where progress is reported only to be retracted or not replicated in other labs.

- A superconducting material will repel magnetic fields and a telltale sign of one is it will float above a magnet and stay suspended in place, even when it is rotated.

Catch up quick: Two preprint papers, which haven't been peer-reviewed, posted by researchers in South Korea outlined their process for using lead-apatite and copper to produce a new superconducting material — LK-99. - They also posted a video of a flake of the material partially hovering over a magnet.

- Since then, researchers in labs around the world have tried to recreate LK-99 and simulate whether the reported technique could produce a superconducting material.

Where it stands: Two studies published this week couldn't replicate the reported technique, another reported creating the material and measuring zero resistance but still at a cool -260°F. - Other scientists have run computer simulations of LK-99 and found it had the potential to be superconductive at higher temperatures and ambient temperatures.

- None of this is conclusive proof either way, Cotes says, and the research continues.

- Experts in the field are voicing skepticism and point to several caveats in the original work as well as follow-up studies.

The bottom line: "At the very least, this is a really interesting new material that opens up a new avenue for exploring superconductivity at high temperatures and ambient pressures," Cotes says. |     | | | | | | 3. The future of NSF |  | | | Illustration: Tiffany Herring/Axios | | | | Lawmakers this year are unlikely to meet CHIPS and Science Act ambitions for the National Science Foundation, the agency at the heart of technology research and STEM workforce development, Axios' Maria Curi writes. Why it matters: Funding long-term basic research in key technologies, such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing, falls squarely on the government because a lack of immediate use cases makes it less attractive for the private sector. - NSF has partnerships with companies and philanthropies but, by and large, depends on the government.

Catch up fast: NSF is regarded as the agency around which the science part of the CHIPS and Science Act was built. - The law authorizes a doubling of the agency's budget over five years, funneling money into early-stage research, research infrastructure, international collaborations, new and existing STEM education programs, and a research security office.

Yes, but: The money authorized in the law is not guaranteed and lawmakers in the coming months will negotiate how much to give to the agency. Threat level: Congress is in for a fight when lawmakers get back from recess in September, and it could lead to a government shutdown. - There's relative bipartisanship on funding tech and science research, but House Republicans' mission to cut government spending overall is bound to affect an agency like NSF.

- The House appropriations bill would prohibit funding for the NSF's Global Change Research Program, Clean Energy Technology program, Advancing Informal STEM Learning Program, Alliances for Graduate Education and the Professoriate Program, and the Office of Equity and Civil Rights.

- A provision in the House bill prohibiting funding to carry out an Office of Science and Technology Policy memorandum to ensure free, immediate and equitable access to federally funded research would also hit NSF.

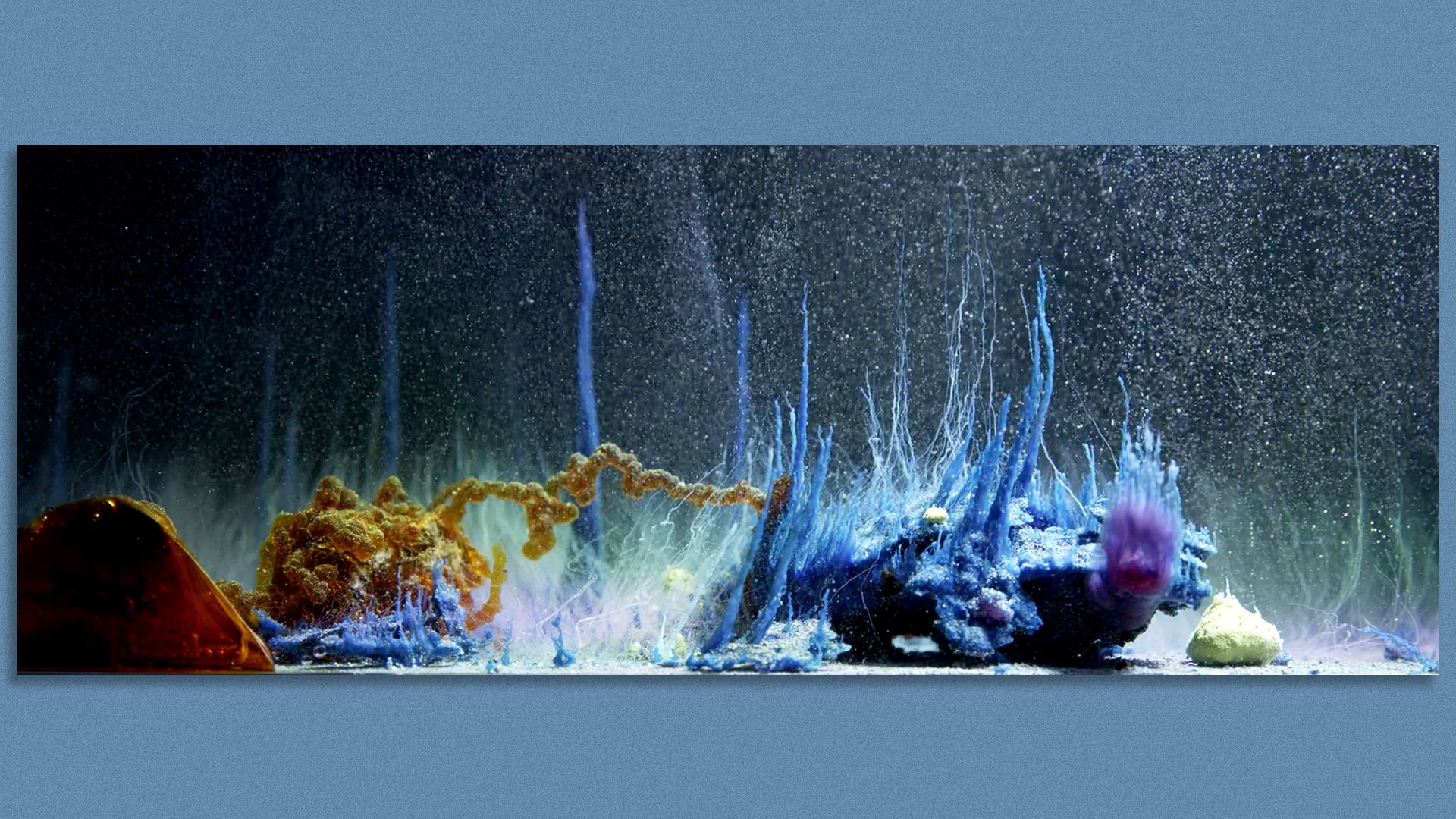

What we're watching: While there's a long way to go, some senators are exploring supplemental legislation to bolster Defense Department spending, which could include a second China competition package with additional funds for an agency like NSF or the National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource, one source told Axios. A version of this story was published first on Axios Pro. Subscribe here. |     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | The Axios Today podcast | | |  | | | | Catch up on the important news and interesting stories you won't hear anywhere else with host Niala Boodhoo. Each weekday morning, get the latest in everything from politics to space to race and justice. Listen now for free. | | | | | | 4. Worthy of your time | | This whale may be the largest animal ever (Dino Grandoni — Washington Post) JWST spies more black holes than astronomers predicted (Alexandra Witze — Nature) Climate change puts children's health at risk now and in the future (Aimee Cunningham — Science News) |     | | | | | | 5. Something wondrous |  | | | "Présage," 2015. Hicham Berrada. Chemical landscape evolving in a glass tank, light. 37x28x5cm. Photo: Laurent Lecat | | | | Artist Hicham Berrada takes an experimentalist's approach to make images from metals manipulated by different temperatures, solutions and other parameters to probe the nature of matter. The intrigue: Berrada says the environments he constructs, where metals move at different tempos, come from his "fascination for the future or places where humans can't live anymore." - "I'm not fascinated by living things — I like the shapes and movement in minerals," Berrada says.

How he works: Berrada uses metals — in "Présage," it is types of iron, copper and magnesium, in "Permutations," it is hardware from old computers — and a palette of parameters to create movements of the metals. - He varies the solutions he places the metals in, the temperature of the environment, and whether he melts the metal before he pours it into its space.

- He'll record the results from one set of conditions, observe the video, take notes and repeat the experiment, changing one variable at a time, a mantra of lab experiments.

- Once the metal's movement in one reaction is optimized to the artist's eye, he adds others one at a time, finally creating a scene that unfolds in real-time and natural color. "Présage" is on view at the Pinault Collection in Paris until October.

- "I see myself as a director of movie or theater," he says. "And the actors are matter."

What's next: Berrada is beginning to experiment with gold and other precious metals. - Gold "doesn't suffer from time and in human history it is interesting from the point of view of belief in different civilizations."

The big picture: "You can see them as something close to catastrophe where nothing is alive [or] would live but nature still makes forms and lives," Berrada says. - "Without humans, it is still nature and always making shapes."

|     | | | | | | A message from Axios | | The Axios Today podcast | | |  | | | | Catch up on the important news and interesting stories you won't hear anywhere else with host Niala Boodhoo. Each weekday morning, get the latest in everything from politics to space to race and justice. Listen now for free. | | | | Big thanks to editor Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath and copy editor Carolyn DiPaolo. Sign up here to receive this newsletter. |  | | Are you a fan of this email format? Your essential communications — to staff, clients and other stakeholders — can have the same style. Axios HQ, a powerful platform, will help you do it. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

To stop receiving this newsletter, unsubscribe or manage your email preferences. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |

No comments